WEEKS ahead of the Zimbabwe election, the battle for votes is being fought as much at the rallies as it is on mobile phones.

Attack ads, campaign videos, WhatsApp blasts, Facebook Live and even fake news are combining to make this Zimbabwe’s first social media election.

On Thursday, pictures of police officers queueing up to place their postal ballots went viral, springing the opposition MDC Alliance into sending its officials to Ross Camp in Bulawayo to counter what they said was rigging. Within hours, videos of opposition alliance officials counting postal ballot envelopes were circulating widely, accompanied by running commentary from both sides of the divide.

There has been a lot of other viral content in this campaign, but this episode showed that Zimbabwe is holding an election at a time the country’s social media has come of age. The last election in 2013 had the likes of Baba Jukwa and their sensational political gossip, but 2018 may be the year that content generated by rival parties and their supporters drives the campaign.

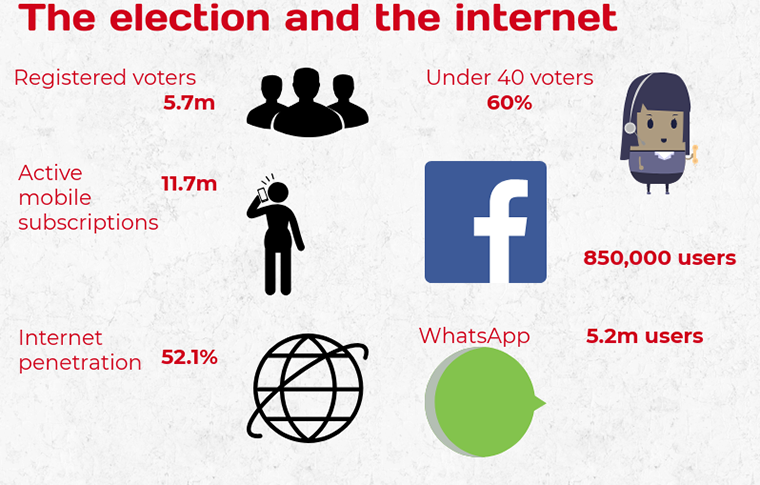

There are 5.7 million voters, 60 percent of whom are aged 40 and under. This election is being held at a time Zimbabweans are now more connected to the internet than ever. WhatsApp has become a beast since the last election, and Facebook and Twitter usage have risen sharply.

Data from telecoms regulator POTRAZ shows that internet access continues to grow steadily. In the first quarter of 2018, there was a 3.8 percentage increase in active internet subscriptions. The active internet penetration rate was 52.1 percent, slightly up from 50.8 percent in the last quarter of 2017. In total, we have over 11.7 million active mobile phone lines.

Data on usage of social media by platform is unreliable, but POTRAZ says close to half of Zimbabwe’s data usage is spent on WhatsApp. A 2017 estimate by tech bloggers TechZim put the number of WhatsApp users in Zimbabwe at 5.2 million. Other estimates say there are over 850,000 Facebook users in the country.

With such numbers, no party is leaving anything to chance.

For the first time ever, Zanu PF, whose traditional tools have been grassroots mobilisation, patronage, violence and intimidation, has invested heavily on a digital campaign.

President Emmerson Mnangagwa is a 76-year-old from the old school, who admitted at the start of his presidency that he knew very little about technology.

But his campaign is running a well-crafted digital strategy; from sleek campaign videos to WhatsApp audios, his #EDHasMyVote campaign is trying to dominate a field that Zanu PF has previously never taken too seriously.

In June, Mnangagwa launched an android app, which sends a campaign update each morning. The app has a tool that connects voters via WhatsApp to the Zanu PF parliamentary candidate in each constituency.

Mnangagwa’s team also sends out a daily election countdown flyer, carrying a quote from him.

But Zanu PF’s digital campaign has not been without controversy. Earlier this week, voters got SMSs from Zanu PF candidates in their constituencies. The opposition accused the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) of releasing voters’ phone numbers to the ruling party. ZEC denied it.

Zanu PF legal secretary Paul Mangwana feebly claimed that the party had only sent messages to its own supporters. ICT Minister Supa Mandiwanzira said the texts may have come from a hacked voters’ roll, which included phone numbers, which he said had been posted online. ZEC has been unable to shake off claims of collusion with Zanu PF.

There is still no explanation as to what happened. However, earlier this year, ZEC disclosed it had detected and prevented an attempt to hack into the servers storing voter registration data.

The SMS scandal points to the darker side of the digital wars. Fake news, attack ads and memes have also occupied the space, which is not entirely unexpected in a country where fake news and polarisation thrive.

A report by free expression watchdog Freedom House says online manipulation and disinformation tactics played an important role in elections in at least 18 countries since 2016. In Kenya, a survey showed that 90 percent of voters had come across fake news.

Mainstream media and social media users will have to filter for facts more than ever before.

Shut out from a partisan state media, the opposition MDC Alliance has stepped up its own digital platforms. Nelson Chamisa, the MDC Alliance candidate, broadcasts all his rallies on Facebook, and has this week begun what he calls “live Facebook rallies” every Monday evening.

The MDC Alliance has led on attack ads, sending out a flurry of quick videos that attack Mnangagwa’s record in Government, his role in Gukurahundi and the 2008 election violence.

Now the question is on how social media will be used on voting day itself, and what impact it might have on the poll. Research into whether social media significantly shifts voting patterns is inconclusive.

However, what is clear is that with the internet now more accessible to more people and in more areas than in previous elections, any cases of voter fraud, intimidation or violence will be a lot harder to hide. Pictures and videos now go viral literally within minutes.

At a march against ZEC, Chamisa threatened to release his own results. With results posted outside polling stations, social media will be awash with shots showing who won and lost where. Rival supporters will post results that drive their agendas. We saw this during the Zanu PF primaries, when partial vote tallies were used to declare false results on social media.

Is ZEC prepared for all this?

The commission has no active online presence, unthinkable in this era of social media. The commission’s Twitter feed is lifeless and does not interact with voters, and it often goes for days with no updates, even in the midst of crises. ZEC has no visible presence on Facebook, which could provide a large audience for the commission. The ZEC website is not updated quickly enough and is not optimised for mobile, yet 98 percent of Zimbabweans access the web via their mobile phones.

ZEC’s social media ineptitude is surprising, given that a social media strategy was part of the 2018 budget agreed with UNDP. A joint project document for the election said social media would be key in “increasing the integrity of the election”. UNDP offered to fund this.

“Outreach mechanisms should always be revisited as communications technology are never static, and digital media outreach should not go underutilized for Zimbabwe’s upcoming voter education and information campaign. Through the project ZEC will be supported in using social media as a tool for Voter Education and Information,” the project document said.

It is unclear why this was not implemented for the 2018 election.

ZEC has been left with no capacity to respond to relentless attacks on its credibility by armies of well-resourced social media influencers, raising questions about its capacity to handle the flood of negative posts that are inevitable around election day.

Will government react by clamping down on the web? It has happened before. In July 2016, social media was shut down during protests led by the #ThisFlag movement. Several African governments have in recent times restricted social media access during elections.

With elections coming up, internet usage is seen rising.

“Upcoming elections are likely to spur the usage of social media and data services, thus increasing the volume of internet usage,” POTRAZ says in its latest report.

For ZEC, it is not too late to step up its social media presence.

For candidates, the winners of the social media war will not be those that use social media only to win arguments and spread propaganda online. Beyond the videos and apps, the winner of this social media battle will be whoever uses it to get their voters out to vote on July 30.

This article was originally published by NewzWire.Live