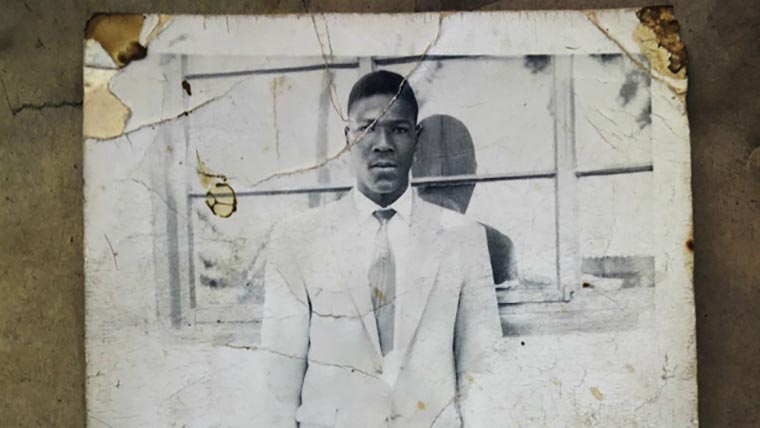

SILOZWI, MATOPO – Julius Mvulo Nyathi, a middle-aged man with a child on the way, was walking home one evening in 1984 when the 5th Brigade snatched him.

Nyathi, and another man taken on the same day – Simimba Nkomo – were never heard from again.

A couple of years passed, and 20,000 killings later, the Fifth Brigade was withdrawn from Matabeleland, leaving a quiet unease that lingers to this day. Emmerson Mnangagwa, one of the enforcers of that atrocity, then the State Security Minister, is now Zimbabwe’s President elect, his narrow victory last week punctuated by more bloodshed – the shooting death of seven people by soldiers during an opposition protest. Over a dozen others have varying degrees of injury. One, deaf and dumb, still has a bullet lodged in his shoulder.

Gukurahundi, a reign of terror that visited Matabeleland and the Midlands by the red-bereted troops between 1983 and 1987, remains a festering wound. And as if by some wicked coincidence, Saturday, August 4, saw the burial of army victims killed three decades apart.

In Harare and surrounding areas, they were laying to rest some of the seven, cut down in broad daylight by death squads in army uniform. Some were bayoneted. Unlike Gukurahundi, this massacre was televised – thanks to hordes of local and foreign journalists, as well as citizens armed with smartphones.

In Silozwi, 50km south-west of the second city of Bulawayo, they were laying to rest a man who died from the same instruments as those whose lives were cut short in Harare, at the hands of the same brutal cast 34 years earlier. It would have been his 86th birthday.

Nyathi – whose body had been buried in a shallow grave on a hill – had his remains exhumed two months ago after the family, supported by local traditional leaders, battled for years to be allowed to go ahead with the reburial.

The family had been led to the shallow grave by one of the men abducted on the same day. He finally mustered the courage after bottling the secret for years. Nkomo’s family attended the exhumation, hoping he was also buried in the same hole on the hillside, only to be disappointed when the remains of one person were found, later forensically proved to be Nyathi’s. Their torment continues.

The most authoritative report on the Matabeleland killings is “Breaking the Silence,” published in 1997 by Zimbabwe’s Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace and the Legal Resources Foundation, drawing on interviews with more than 1,000 people and many documents.

Much remains to be done to heal the scars of the killings, said Shari Eppel, the report’s main author, who continues to do forensic research into the killings as director of the Solidarity Peace Trust. Her organisation is assisting families who want to give a proper burial to family members who died during Gukurahundi.

“Julius Mvulo Nyathi died in 1984, which was when the 5th Brigade was deployed in Matabeleland South,” Eppel said. “We heard that his arms and ankles were tied with wire and he was severely beaten by the 5th Brigade, soldiers who came in uniforms with red berets and accused him of being a dissident… He also had burning plastic dripped onto his legs and he was then dragged away.

“Nobody actually saw his death, but his body was found in the hills and he was buried in a shallow grave above a secondary school in Matopo district.”

The man who led the family to Nyathi’s body did not survive to see Saturday’s reburial. But two other witnesses, given a few minutes to speak, had some of the mourners in tears as they relieved Nyathi and Nkomo’s last few hours.

One of the survivors, who was 13 when he was taken, is still trying to understand why he was targeted.

“Who would want to harm a 13-year-old? Then I remembered that in Srebrenica [during Bosnian War], they butchered little boys as well,” he said.

Another of the survivors recounted how Nkomo and Nyathi were repeatedly beaten and kicked until they collapsed, and could offer no further resistance.

“I’m overcome by sadness that the same guns that were used to kill my fellow villagers are being turned on civilians again,” he said of the street massacre in Harare.

Villagers listened in shock as they heard how Nyathi’s skeletal remains told a story of his demise.

His ulna, the long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, had been broken on both hands – suggesting he was using his arms to try and stop the beatings.

His trousers showed signs of having come into contact with a fire, and one of his fingers was broken, the forensic report said.

One foot and one hand were missing, possibly the work of wild animals. One tooth was chipped, likely from a blow to the mouth.

The pastor read from Genesis 50 verses 5-24. He likened Nyathi to Jacob and his son, Joseph. He had lain in the wilderness waiting to go to Canaan to be taken home and be home.

“Like Joseph, he waited 34 years and today we have brought him home. May you rest in peace,” the preacher said.

Tragedy, for the Nyathi family, was mitigated by the birth of his son that same year. His widow, who was at Saturday’s reburial, was blessed with a boy, Chris, who now lives in Botswana and “moved mountains”, according to the family, to ensure his father – a man he never knew – got a decent reburial.

Isaia Nkomo, 60, remains unsettled by the death of his brother, Simimba, 34 years ago.

“I was at work, in Bulawayo, and my brother was at home in the village. So they came and took him from our homestead and killed him in the bush,” said Nkomo. “We still haven’t located the place where he is.”

His family, he said, is “not feeling well because we keep thinking about him. Other people’s remains have been found and we are still looking for him. He might have been eaten by wild animals or some other people removed him and put him somewhere else.”

Nkomo did not vote for Mnangagwa or Zanu PF.

“Voting for Mnangagwa, I can’t do that because my brother was killed at that time by the people who currently want us to vote for them, those that are in power. I’d rather vote for someone in the opposition.”

Eppel said many in Matabeleland say the region is haunted by “angry dead.”

“The angry dead are the people buried in the wrong place and who haven’t had the right rituals at the time of their murder and burial,” said Eppel.

She said hundreds of reburials are needed to assuage families: “People say these angry dead are the ones who make bad things happen in the family and the community, to keep reminding them; ‘I’m in the wrong place, I need to come home.’”

The army’s Operation Gukurahundi — “the early rains that blow away the chaff,” in Shona language — ran from 1983 through 1987, when the Fifth Brigade rampaged through the southwestern provinces of Matabeleland and the Midlands, targeting mainly Ndebele speakers.

The residents of villages were rounded up and forced to attend all-night rallies for Zanu PF. Community leaders were beaten and sometimes killed in front of the gatherings. Men, young and old, were forced to dig graves, then shot and buried in them. Survivors were forced to dance on top of the fresh graves, sometimes until the blood of the dead seeped through.

Some families were pushed into huts that were set on fire and they either burned to death or were shot dead when they tried to escape.

The Fifth Brigade consisted of 3,000 troops, virtually all ethnic Shona, who make up about 70 percent of Zimbabwe’s population. The brigade received counter-insurgency training by North Korean advisers and was known as the elite praetorian guard of former President Robert Mugabe, directly answerable to his office. Their arms and uniforms were different from the rest of the army, including their distinctive red berets.

With its prolonged, deadly campaign in Matabeleland, the Fifth Brigade was trying to stamp out rural support for anti-government rebels. Gukurahundi also was viewed by many as an attempt by Mugabe to weaken any opposition to his stated aim of a one-party state.

The army’s campaign did not succeed in winning the Ndebele vote for Mugabe in the 1985 polls or succeeding elections.

MDC Alliance senior leader David Coltart said there was enduring resentment across Matabeleland.

“What we need from Mnangagwa is an admission of what happened, an apology and communal reparations for the victims of that time,” said Coltart. “I’m not convinced that prosecuting someone like Mnangagwa is going to heal our nation at this time.”

Those at the head of the chain of command have not been held to account. Mugabe never accepted responsibility or apologised for the killings, but he did call them a “moment of madness.”

Mnangagwa has also refused to accept responsibility and has opposed a new investigation, saying it would re-open old wounds. Perence Shiri, the head of the Fifth Brigade during the killings, rose in power to become the head of Zimbabwe’s Air Force and now is the Minister of Agriculture, appointed by Mnangagwa.

Additional reporting Associated Press and Mandlenkosi Mpofu