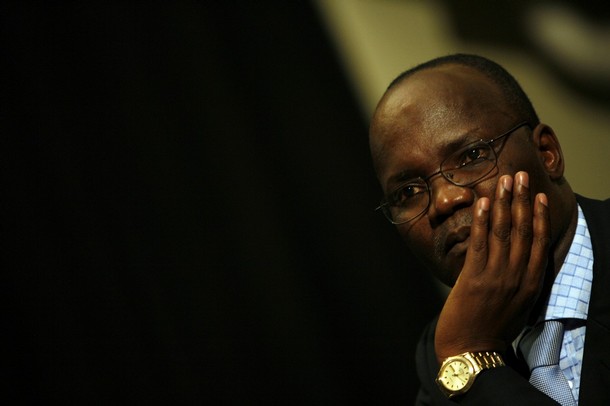

A year after a military coup that ousted former President Robert Mugabe from power, and forced him into exile, former Higher Education Minister Professor Jonathan Moyo reflects in an interview with the Big Saturday Read blog run by academic Alex Magaisa

BSR: Thank you, Professor Moyo for agreeing to do this exclusive interview with us at the BSR as we approach the anniversary of the events which ousted former President Robert Mugabe’s government. Some firmly believe it was a “military coup”. Others prefer to call it a “military-assisted transition”. For months you were intimately involved in the events that culminated in that dramatic chapter in Zimbabwe’s history, so it is in the public interest to hear your reflections. One year on, which label best describes those events: military coup or military-assisted transition? Why is this characterisation important?

ANSWER: First, thank you for giving me this BSR opportunity for a conversation on the first anniversary of the momentous events of November 2017, in which tanks and bullets altered and redefined state politics in Zimbabwe in dramatic and fundamental ways whose import is yet to be fully appreciated. Second, congratulations on your excellent BSR initiative. You have done commendably well in developing the BSR into a go-to platform on Zimbabwean issues. The BSR has become the meeting-space of choice for Zimbabwean minds and others interested in everyday history around the country’s political economy and constitutional challenges.

As for me doing this BSR interview, I must say I initially thought twice about it and I was inclined to think against it. This is because I am currently working on two different but complementary books: one an autobiography (expected to be published in 2019) and another a major academic memoir (expected to be published in 2020) on state politics in Zimbabwe from 1979 to 2020. Both books extensively deal with the antecedents, facts and consequences of the November 2017 coup including some related to the BSR questions you say you want to raise with me. The autobiography focusses on my personal and political experiences while the academic memoir retraces and unpacks Zimbabwe’s state politics between 1979 and 2020 and projects it into the future by describing and interpreting the record against the backdrop of the best of competing political theories with the 2017 coup as the power point of the book. In the end, and tempted as I was to say “no, wait for my books”, I thought it would not be a worthy excuse to decline this BSR conversation on account of two books in progress.

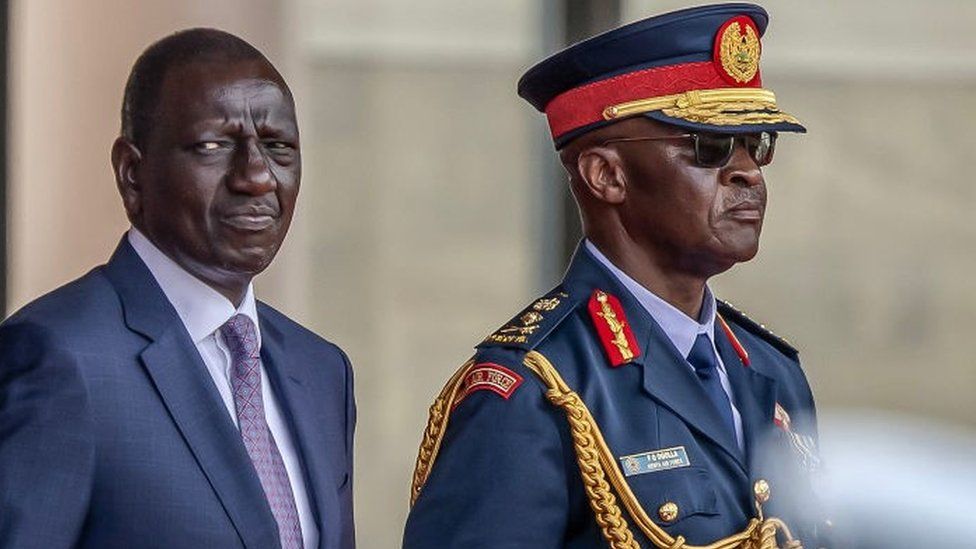

And to your question as to which label best describes the events surrounding the ouster of former President Mugabe and his government last November, in what was initially claimed to be “a coup that was not a coup”; I’m aware that, as you suggest, there’s a debate whether the events were a “military coup” or a “military-assisted transition”.Based on what I know happened, how it happened, who was behind it and so forth, I can say quite categorically that the events of those two weeks in November 2017 were indubitably a military coup. The events were triggered, moved and shaped by tanks and bullets with the generals calling the shots. The country fell under direct military rule, especially from 13 November 2017 to 18 December 2018 and has since then effectively remained under the military. As we speak, and despite some optics to the contrary, Zimbabwe is under military governance. Before the 30 July 2018 general election, General Constantino Chiwenga publicly declared that “Operation Restore Legacy”, used by the Army to justify the coup, would remain in force until Mnangagwa won the 30 July election.

But as is well known, Mnangagwa did not win the election and the exact result that the Zimbabwe Election Commission (ZEC) declared on his behalf remains unknown to this day, notwithstanding the controversial Constitutional Court decision that endorsed the ZEC declaration, without saying which of the three and conflicting results declared by ZEC the Court was endorsing and why. In any event, all the three conflicting results declared by ZEC and endorsed by the Constitutional Court showed that half of the electorate did not support Mnangagwa. This point should be emphasized. Mnangagwa does not have the majority support of the electorate and that is why he has a legitimacy crisis. He is a divisive leader with divided support in power only because of the military that installed him in the first place.

Mnangagwa’s crisis of legitimacy cannot be cured by referring to Zanu PF’s two thirds majority in Parliament.Zimbabwe is a constitutional democracy and not a parliamentary democracy. The head of state is elected directly by the people and thus does not come from parliament as is the case, for example, in South Africa or in parliamentary democracies in the Commonwealth. The military is of course aware of this and the implications thereof. The fact that Mnangagwa has a clear and present crisis of legitimacy, with at least half of the voters having rejected him by ZEC’s disputed declaration, has impelled the military to stay put to deal with the precarious situation with respect to order and stability. Without the military in control of political power, Mnangagwa would not last a day in office.

As such, the situation that obtains on the ground cannot be characterised as a transition of any kind. In this regard, there’s no military-assisted transition in the country. If anything, there’s a stalemate or an arrested transition.The correct characterisation of the situation as either a military coup or a military-assisted transition is important in order to shine some light on the way forward, regrading the necessary reforms. Where you have had a military coup, there can be no transition, and here I mean a democratic transition, without curing the coup. No military coup has ever assisted, or paved the way for, a democratic transition.

BSR: You have always argued that what happened last November was illegal and unconstitutional change of government. You averred that the Mnangagwa administration that took over in November was illegal and illegitimate. Assuming that was correct, could it be argued that the alleged illegality and illegitimacy were cured by the general elections on 30 July 2018? In other words, do you now accept that the Mnangagwa administration has both legality and legitimacy?

ANSWER: Yes, it is common cause that what happened last November was illegal and unconstitutional. The contrary declarations by the High Court and Constitutional Court will not survive history. Those declarations will be set aside in due course.

So, no, I do not accept that the Mnangagwa administration has both legality and legitimacy by dint of the 30 July 2018 elections. The 30 July elections bestowed on Mnangagwa only a veneer of legality, not in terms of the rule of law but in terms of rule by law. The legal rules that were used to organise and run the 30 July elections were superintended by a coup government that came into power via the gun. The military was fully behind the conduct of ZEC and organs of the state in the preparation for and conduct of the 30 July elections.

It was impossible for any civilian to raise a finger against the military between 13 November 2017 and 30 July 2018, let alone now.Add to this the documented fact that the military deployed and embedded serving and retired soldiers across all communities in Zimbabwe. These soldiers became a law unto themselves in the rural areas. It is also a fact that the military took over key security organs, notably the Police, National Prosecuting Autority and even elements of the judiciary.

Against this backdrop, legality flowing from imposed or decreed law by the coup government, an illegitimate authority, is problematic and unsustainable. Put differently, no legitimate outcome can result from an illegitimate action. The coup government took effective control of the country by force, but that control did not become legitimate on account of its effectiveness. A hijack does not become legitimate or legal by virtue of its effectiveness. The matter would have been different had the coup resulted in an all-inclusive government whose first order of business would have been to restore constitutional governance, and which would have prepared for free and fair elections in accordance with the Constitution.

As for the 30 July 2018 general election, the preparation for that election and the outcome of the presidential election did not yield any legitimacy. In my view, and based on Zimbabwe’s new Constitution, sustainable legality with the force of the rule of law can only come from a legitimate election with a legitimate outcome.

BSR: Many people are intrigued that you and your colleagues in the so-called G40 faction seemed to be oblivious to the onset of the military action on or around 14 November 2017. This seems implausible with all the intelligence apparatus at former President Mugabe’s disposal. On more than one occasion, the former First Lady, Grace Mugabe had made insinuations regarding military intervention. We recall when she cited a passage from the Holy Book about Adonijah’s attempt to usurp power from the ageing King David. Surely you must have been aware or at least suspected that a coup was being planned? If you were aware or suspected it, why did you not take pre-emptive measures? Why did it seem like former President Mugabe and G40 were caught totally unprepared by the military action?

ANSWER: While I appreciate both the import and importance of this question, I think that it exaggerates and misrepresents some key facts and the political situation that obtained before the November 2017 military coup. It is instructive that you refer to “the so-called G40”. And you are correct, it was the so-called. Rather than deny that there was anything called G40, which I have done before but in vain, I think it is important to understand that, as a matter of fact, there was no group or association or faction of like-minded Zanu PF political leaders or supporters who identified themselves as G40, to mean people who shared common values, aspirations or political objectives that they pursued with a common strategy. There was never a thing like that.

Remember that G40 is a label that found political currency only in 2015 when it was repeatedly and creatively used by Stanley Gama when he was editor of the Daily News after his paper could no longer sustain the label of “G4” (Gang of 4) which they had used in 2014 after Rugare Gumbo, then Zanu PF secretary for information, had invoked it to describe Saviour Kasukuwere, Opah Muchinguri, Patrick Zhuwao and myself during the height of the days of “Gamatox” (Joice Mujuru) and “Weevil” (Emmerson Mnangagwa) factions ahead of the ZanuPF’s 2014 Congress. G40, as a political faction of a like-minded people who acted with a common purpose, is a media creation.

After the Zanu PF 2014 Congress, Oppah Muchinguri drifted away and the “G4” became an unattractive label to the Daily News. As an act of creative genius, aware that there was an immediate fallout between Mnangagwa and his cronies on the one hand; and Kasukuwere, Zhuwao and me on the other hand, Stanley Gama opportunistically dusted off an article I wrote for the Sunday Mail in August 2011 on “Generation 40” (G40) as a demographic group across the political divide and used it as a replacement of “G4”.By that time, Mnangagwa’s cronies were affectionately calling each other “Lacoste”, while pretending to be clever and a half with claims that they were referring not to “Ngwena” known in political circles to be Mnangagwa’s nickname but to the green crocodile logo of a French merchandising company. Stanley Gama again seized on this and the Lacoste faction was born in the pages of the Daily News.

Thus 2015 saw the birth of two Zanu PF factions: G40 and Lacoste.While the rest is history, the fact is that this was a gross simplification and a catastrophic misrepresentation of national politics. It cannot be correct that Mnangagwa’s faction started in 2015 as Lacoste. It is also not correct that a new Zanu PF faction, called G40, emerged for the first time in 2015 and grew to be such a big deal that could only be stopped through a military coup in 2017.That is political nonsense. But this is a story for another time and place whose content, nuances and ramifications I unravel in the two books that I am working on.

With all due respect, and while I understand the source of the question, I must say that anyone with grounded information of what was happening, would not ask whether the so-called G40 was aware of the coup and, if they were aware, why they did not take pre-emptive action to nip it in the bud. From a factually point of view, this question should not arise.

There was no group or caucus that met as G40. The saga of G40 was in the newspapers and not in political reality. Many individuals labelled as G40 did not actually get along or trust each other or like each other or plan with each other. What is true is that anyone who did not support Mnangagwa’s succession plan or who was loyal to President Mugabe was labelled G40 as a matter of political stigmatisation. Otherwise, yes, some individuals seen as G40 were indeed aware of the coup, whose planning was long in coming. I certainly knew about the coup and I made representations about it to the politburo and President Mugabe, including in writing and by video documentation.I don’t think there is any substance in asking why individual members of cabinet or politburo, who knew about the military coup, did not do anything to stop the coup. Things don’t work like that in state politics. The real question that people should ask is whether President Mugabe knew about the coup and if he did, why he did not put in place measures to contain or pre-empt it. That is the real question that is blowing in the wind for an answer.

My view is that, although he got various reports from different sources about the planning of the coup, President Mugabe did not believe those reports because he trusted Mnangagwa and Chiwenga more than he trusted those who gave him the reports.It is my considered judgment that President Mugabe genuinely and truly believed that Mnangagwa and Chiwenga would never countenance toppling him from power. It is in this connection that to this day President Mugabe considers what Mnangagwa and Chiwenga did as the great betrayal. In fact, he considers it the utmost treachery.

While I am aware of some political and structural reasons why the coup was not stopped or could not be stopped, it should be said that the November 2017 coup was stoppable, even as it unfolded. Those who did the coup took a risky chance and they were surprised by their luck when the coup was not resisted between 15 and 19 November. By 19 November, President Mugabe believed that the coup would not proceed based on his engagement with Chiwenga who seemed more concerned about his security of tenure and Zanu PF succession which he wanted settled at the December 2017 special Congress. In fact, Chiwenga wanted President Mugabe to remain in office to serve out his term but to handover leadership of the party at a special Zanu PF Congress. In the same vein, Chiwenga wanted the so-called “G40 criminals” who were alleged to be surrounding the President to be dropped from cabinet and politburo and prosecuted for “treason” as a settlement of the military action.

Chiwenga was baying for my head as was Mnangagwa. At the very least, they wanted me prosecuted for what they alleged was treason. That is still their plan to this day, which they have been pursuing under false ZimDef allegations which now include laughable claims that I bought properties with ZimDef funds costing over $3 million citing Pandhari Lodge, a property adjacent to State House and some and bank deposits which ZimDef, teachers colleges and polytechnics lost at Metbank during the inclusive government between 2009 and 2013. The Pandhari Lodge and State House properties were purchased by Washington Mbizvo who was Permanent Secretary long before I was appointed Minister of Higher Education in July 2015.I have wondered why they don’t ask Oppah Muchinguri who, as my predecessor, should know better about these and other properties. I am also baffled why they don’t ask Ozias Bvute and Enoch Kamushinda about over $11 million of ZimDef funds and deposits from colleges and polytechnics that went missing at Zimbank between 2009 and 2013.Fortunately, all this is well documented.

I tell this story in detail in the autobiography I am working on for publication next year under the title, “Letters to My Father”. I know for a fact, especially with documented information that became known after the coup, that if Chiwenga’s soldiers had found me at our home in the wee hours of 15 November 2017, they would have killed me. Part of the evidence for this is how the soldiers were vicious and destructive when they attacked our home and the destruction of rooms and property they did once in the house which they looted and occupied for some 10 days after 15 November. There was no question of arresting me. Chiwenga’s soldiers were on a mission to kill me. Just like the Gukurahundi soldiers killed my father, to whom my autobiography is addressed. The soldiers did not find my family and me at home because I was tipped by other soldiers to evacuate my family from the house and not sleep at our home under any circumstance.

So, while I could not use the information I had about the coup to stop the coup or to pre-empt it, I did use crucial information about the coup to get my family and myself out of assured harm’s way by getting out of our house which had been earmarked as a death trap for me with unknown risks to my family given the excessively violent manner the soldiers attacked and entered our home. I have seen narratives that focus on a tweet I posted on 13 November 2017 directed at Chiwenga and telling him that while he was giving his press conference I was “zete” sleeping at my home.Ignoramuses take that as a sign we did not know a coup was in the making. That banter was precisely because everyone knew there was trouble in paradise.

But to your question, President Mugabe did not believe that Chiwenga would carry out the coup to the point of ousting him from power and he believed this to be the case up to 19 November when he gave the now famous “Asante Sana” speech which left a clear impression that he was not going anywhere.But Mnangagwa and his cronies, supported by some military elements not linked to Chiwenga wanted President Mugabe to be toppled by the Army and they were uncompromising about this. By 20 November 2017 the likes of Paul Mangwana, Patrick Chinamasa and Jacob Mudenda—to mention but three names in Zanu PF—were waving legal scenarios to force Mugabe to resign under threat of getting Parliament to impeach him if the Army strategy was encountering challenges. Again, the rest is history.

In summary, the notion that people were caught by surprise is simply not true.What is true is that specific actions by the Army, many of them which were ad hoc or spontaneous, were of course not known. And it is true that President Mugabe did not believe that Chiwenga and Mnangagwa would lead or be associated with any military action to topple him. I offer reasons for this in the two books I am working on.

BSR: After 37 years in power, President Mugabe seemed to be very comfortable. We saw how often he travelled outside the country as a sign of a leader who had complete command of the military and had no reason to fear a coup. Most leaders who are insecure rarely venture outside the country. President Mugabe was always flying somewhere. On reflection did this give him a false sense of comfort? At what point did he lose grip of the military? Were you ever concerned that there might be a military coup, and did you warn him?

ANSWER: I think I have dealt with aspects of this question and I have indicated that I did warn President Mugabe about the coup to no avail. Let me reiterate. President Mugabe did not believe that Chiwenga and Mnangagwa would contemplate, let alone carryout, a military coup against him. President Mugabe believed that Mnangagwa and Chiwenga were his two most loyal assistants. He had come a long way with them and literally groomed them. I can say that President Mugabe distrusted everyone, and in that regard people like me were top on the list of the distrusted, but not Mnangagwa and Chiwenga. These two were top on the list of the most trusted lieutenants. President Mugabe’s trust of these two predated independence and was cemented in 2008 when there was a handshake whose dynamics played out during the GNU government between 2009 and 2013 when Chiwenga and Mnangagwa were the most critical military engine behind the election campaign that they saw as a prelude to succession in 2018. Between 2013 and 2014, there were no issues about this even between Mnangagwa, Chiwenga and the former First Lady Amai Grace Mugabe. Things changed immediately after the December 2014 Zanu PF Congress and all hell broke loose in 2015. This is a story yet to be told.

BSR: On 1 June 2017, you made a dramatic announcement, throwing the name of Dr Sydney Sekeramayi into the succession race. This was interpreted as an effort to counter your rivals by supporting a candidate with solid liberation war credentials. Some thought it was a pre-emptive move against former First Lady Grace Mugabe who was increasingly perceived and perhaps beginning to see herself as a successor to her husband. Later that month we saw her publicly exhorting her husband to name a successor. On the other hand, President Mugabe was adamant that he would not name a successor. What was the idea behind the Sekeramayi suggestion? Was he aware of what was going on? Was there a consensus among your colleagues over a candidate? Why did President Mugabe not name a successor? Some people think he never wanted to leave. Do you think he was ready to pass on the baton?

ANSWER: Some of us found the presentation of Mnangagwa as the only successor under a claim that there was a pecking order of succession going back to the 1975 Mgagao Declaration as ludicrous and contrary to the fundamental principles of democracy and at odds with both the Zanu PF constitution and the Constitution of Zimbabwe. By June 2017, the Zanu PF special Congress earmarked for December was on the horizon and the idea that Mnangagwa was the only candidate for succession needed to be interrogated. By then President Mugabe had signalled in May 2017 his preference for Sydney Sekeramayi. I put forward Sekeramayi’s name not only because I honestly believed that he was the best transitional leader on offer but also because I was fully aware that Sekeramayi had President Mugabe’s support. And yes, Sekeramayi knew that he had President Mugabe’s support, and he heard this from the horse’s mouth.

But to my shock, soon after I broached Sekeramayi’s name, I learnt that some so-called G40 stalwarts did not support him. The view was that Sekeramayi was a spineless political coward. I came under heavy attack for putting forward Sekeramayi’s name from within “G40” circles with the result that I ultimately said less and less about the proposition; hoping in vain that President Mugabe would come to the rescue and publicly signal his support for Sekeramayi. The fact that Sekeramayi did not grab the opportunity when it knocked on his door, as he remained the reluctant one, did not help matters. In the end, confusion reigned supreme as some comrades with fatal ambitions took advantage of that confusion to advance dangerous propaganda that President Mugabe was the party’s 2018 presidential candidate. This is also a story yet to be told.

BSR: Mrs Mugabe took centre stage in the firing of both vice presidents, Joice Mujuru in 2014 and Emmerson Mnangagwa in 2017. It worked in the case of Mujuru but backfired spectacularly in the case of Mnangagwa as the tables were turned against Mugabe. Many people thought Mrs Mugabe took it too far in both cases. You went along to most of her rallies and many saw you as the brains behind the instrument that she was. Were her actions part of the plan or she was a loose cannon? Did you have any misgivings about her approach? Did you ever try to restrain her?

ANSWER: I am aware of the view that Mrs Mugabe took centre stage in the firing of both Joice Mujuru in 2014 and Mnangagwa in 2017 but I think the view is not entirely correct. The movers and shakers and the brains behind the firing of Joice Mujuru in 2014 were Chiwenga and Mnangagwa. They did this as part of their 2008 succession handshake. Mrs Mugabe was their recruit in 2014 but she was not the main player. It’s important to understand that in 2014, Chiwenga, Mnangagwa, and President Mugabe acted in and with a common purpose against Joice Mujuru in 2014. While Mrs Mugabe did hold rallies and said some tough and even nasty things against Joice Mujuru, she did not take centre stage in Mujuru’s firing. The three men did the job with a supporting cast that had others, including me as then information minister. This too is a story yet to be properly told.

The 2017 scenario was different, and indeed Mrs Mugabe took centre stage in the firing of Mnangagwa on 6 November last year. It’s news to me that you say many saw me as the brains behind Mrs Mugabe. But the presumption that anyone, especially a person like me could become the brains behind Mrs Mugabe is preposterous and can only come from people who know nothing useful about Mrs Mugabe and especially about President Mugabe. Becoming the brains behind Mrs Mugabe would have meant coming between the President and his spouse. That would have been reckless and suicidal.This equally applies to the notion that I should have restrained Mrs Mugabe. As who? Surely, only her husband and family members could do that. In any event, my respect for President Mugabe would never have allowed me to poke my nose into his family. Never. People who say the nonsense that I was the brains behind Mrs Mugabe or that I should have been the one to restrain her must know that I did not go to school only to come out as naïve as suggested by their nonsense.

Otherwise, clearly many things went wrong last year. Many. A lot that was said and done at those interface rallies was unwise and most unfortunate, not least because it gave hostage to fortune.

BSR: During the offensive against Mujuru and her faction in 2014, you all seemed to be united, including Mrs Mugabe, Chris Mutsvangwa and Mnangagwa. However, no sooner had Mnangagwa settled into office as the new Vice President than factions began to emerge, and the fights started again. What was the cause of the quick fallout? Did you not know that the fall of Mujuru would open the way for Mnangagwa which would place him in pole position to succeed Mugabe?

ANSWER: As I have already indicated, it is not correct to say factions began to emerge no sooner had Mnangagwa settled into office as one of the two vice presidents. Factions preceded Mnangagwa’s elevation to the vice presidency. But I think the important question you ask is whether we knew that the fall of Joice Mujuru would open the way for Mnangagwa and place him in pole position to succeed Mugabe. Frankly, we did not know that. More accurately, I should say I did not know. And here is why.

It is important to understand that the Joice Mujuru saga in 2014 directly pitted her against President Mugabe. The proverbial system presented her as using her position as vice president to fight President Mugabe to force him out of office. Throughout the Mujuru saga in 2014, there was never an indication that Mujuru’s ouster would open a door for Mnangagwa. This is because it was always clear that Mujuru’s replacement, in the event she was removed from office as vice president, would be Oppah Muchinguri. This was the deal. The idea that a man would replace a woman was a no, no. We all understood that.

More significantly, I drafted the amendments to the party’s constitution ahead of the Zanu PF December 2014 Congress. I did the drafts for Mnangagwa and Chiwenga who would comb through them and cause me to redraft 70 by 70 times. I used to have endless meetings with Mnangagwa at his office, many more with one of his assistants but most of the meetings were between Mnangagwa, Chiwenga and myself at Chiwenga’s house or at some house used by Mnangagwa on Churchill Avenue, just after Second Street towards Avondale.During the drafting, the only position that was contemplated for Mnangagwa was that of Prime Minister in government and National Chairman in the party. But the Vice Presidency was always going to Oppah Muchinguri, for her to replace Joice Mujuru.

Closer to the December 2014 Congress, about two or so weeks, inexplicable concerns started mushrooming about Oppah Muchinguri’s suitability as a replacement for Joice Mujuru. Mnangagwa asked me to remove from the amendments we were working on, the provision that “one of the two vice presidents shall be a woman”. He said this was a directive from President Mugabe. This was the bombshell that caused the fallout. I could not believe my ears. I did as I was directed and from then on, the draft amendments were not sent back to me as had become the approach but were finalised between Mnangagwa and Patrick Chinamasa with Mnangagwa saying he was working directly with President Mugabe.

BSR: Many people were concerned that Mrs Mugabe was on a relentless drive to succeed her husband. When we wrote the story of Mamvura driving the bus, it was because there was a clear possibility that she could take control of the bus and yet she seemed ill-equipped and ill-experienced for the job. Did you understand people’s concern that she could actually end up on the wheel? Do you think she was ready to drive the bus?

ANSWER: I think every rational person understood the various permutations and possibilities but none of them justified a military coup. The proposition that the coup was done to stop Mrs Mugabe from succeeding her husband is uncivilised and undemocratic. But on whether I understood people’s concerns that Mrs Mugabe could have ended up on the wheel, the answer is yes, of course I did. How could I not? I however think that people should have been equally concerned about Mnangagwa ending up on the wheel. The fact of the matter is that Mamvura is now driving the bus.

BSR: Some people cannot understand how you fell out with Mnangagwa. They believe you were close to Mnangagwa in the period leading to the famous Tsholotsho Declaration which was supposed to push the agenda for Mnangagwa’s ascendancy to the ZANU PF vice presidency following the death of Vice President Simon Muzenda. You have denied that you were central to that plot, but you were punished for it. Some people think you never forgave Mnangagwa for failing to defend you. Did you feel betrayed by Mnangagwa? Is there any truth to these claims? What is the actual source of the bad blood that manifested so openly after he became Vice President?

ANSWER: The claim that I was close to Mnangagwa in the period leading to the so-called Tsholotsho Declaration is a myth which exposes the lack of factchecking in the Zimbabwean media and scholarship. It’s simply not true. There’s no corroborating evidence to support that claim. Nobody can point to any gathering or meeting or activity that links me with or in which I participated with Mnangagwa prior to the prize giving event at Dinyane High School. A swallow does not make a summer.

It does not make sense for people to conclude that I was close to Mnangagwa on the strength of one event that I became associated with by virtue of coming from the district where the event was held.Prior to the Dinyane event, there was a similar speech and prize giving event at Ntalale High School in Matabeleland South which I did not know about until after the fact. There were other Mnangagwa events elsewhere around the country and I attended none of them. So how did I become close to him simply by attending the Tsholotsho event? Add to this the fact that I was not on the panel of speakers at the Tsholotsho event, whose leading lights were Patrick Chinamasa, Jacob Mudenda and Josiah Hungwe. Claims that I have ever been close to Mnangagwa are legion yet fanciful.

My beef with Mnangagwa is rooted in his direct, instigatory and supervisory involvement in Gukurahundi atrocities; and his leading role in the enforcement of the Rhodesian State of Emergency from 1980 to 1990. While the Fifth Brigade was specifically created for genocidal purposes against Zapu and Ndebele people; and while arguments have been made to distance Mnangagwa from the Fifth Brigade under claims that he was not in charge of the army; the fact is that atrocities in Matabeleland started well before the deployment of the Fifth Brigade with Mnangagwa’s Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) as the frontline perpetrators of those atrocities. Under Mnangagwa the CIO was a killing machine, especially in Matabeleland where the cold-blooded killings followed gruesome torture.Even after the Fifth Brigade was deployed, it is Mnangagwa’s CIO that used to make indications of targets for the Fifth Brigade and CIO operatives used to participate in the torture and killings together with the Fifth Brigade. This is documented history.

The fact that Mnangagwa did not defend me when I was punished for attending and supporting his Dinyane High School event in Tsholotsho is not an issue to me.President Mugabe thought it was an issue on account of my anger when I narrated it to him and the politburo last year. Prior to that angry narration, Mnangagwa had openly threatened to kill me, after I presented a video on his and Chiwenga’s coup plot in the politburo in July 2017, by declaring to the politburo that the best way deal with people like me is to do what they used to do to “sellouts” in Maputo whose necks used to be separated from their shoulders. Mnangagwa’s threat to me was also a confirmation of his murderous deeds in Maputo. I sat in the politburo looking at him and thinking of what happened to my father and I got very angry, leading to my angry outburst which was referenced by President Mugabe.

All said, my considered judgment has always been that Mnangagwa is not presidential material. He is a very cruel person and his threat to separate my neck from my shoulders in the politburo and his boast that they used to separate necks from shoulders of comrades in Maputo is an example of extreme cruelty and barbarism. While he is clearly streetwise, he’s not a statesman by any stretch of the imagination.

National and world leaders are well read people of letters. President Mugabe was and still is a man of letters. He is a well-read gentleman. I have always wondered whether Mnangagwa has ever read any book besides school and college textbooks he had to read as a student. You can tell whether a person reads books by their speech.People who read books are great speakers and great thinkers.Mnangagwa is not in this category.In any event, it cannot be right that a person who oversaw the CIO during the Gukurahundi days and the state of emergency when the CIO was a killing machine that used extreme torture methods can become a president of a constitutional democracy. It just cannot be. It is not surprising that it took a military coup for Mnangagwa to become president.He had no other path.It is also not a surprise that the same military stole the election for him. Again, he had no other path.

I should add here that between 2010 and 2014 I became very close to Chiwenga. Very close. We worked together between 2010 and 2012 to try and bring a Chinese company to mine gold in Tsholotsho with a condition that the company would build the Tsholotsho-Bulawayo road. The project almost succeeded. I was pained that it did not. In 2013, I worked with Chiwenga to manage potential explosive political issues that arose after the Zanu PF primary elections. It is Chiwenga who supported my work to put together the Zanu PF campaign team for the 2013 elections and to resource the campaign team. I spent a lot of time on the national campaign working with Chiwenga in Harare and ended up going to campaign Tsholotsho North only 10 days before the election.

When I lost the election, and I told Chiwenga of the result, he advised me to forget about it and to return to Harare immediately where there was lots of work for me to do. When I was appointed to the cabinet in 2013 as one of the five members appointed from outside Parliament, I had no doubt that Chiwenga had put a pivotal recommendation based on the work I did in leading the 2013 Zanu PF national campaign in Harare. President Mugabe said as much to me.I continued to work closely with Chiwenga from 2013 to December 2014.

Things dramatically changed after the December 2014 Zanu PF Congress that elevated Mnangagwa to vice president. Thereafter, each time an issue came up about the party or government, Chiwenga would ask me if I had checked with “Shumba”. Suddenly, everything was Shumba this and Shumba that. I was uncomfortable and unwilling to subject myself to the Shumba regime when my appointing authority was President Mugabe. I was also aware of the shenanigans that had taken place for Mnangagwa to become vice president ahead of Muchinguri. My unwillingness to subject myself to the Shumba regime is the reason there was a total and complete fallout between Chiwenga and me. He was outraged by my refusal and I was outraged by his insistence.This was very sad and tragic. The rest is history.

BSR: There is a widespread belief that it was a bloodless coup. However, you have challenged this claim. There have been whispers that it was indeed bloody, but no one has been forthcoming with specific details. What more can you tell us about the casualties of the coup? Is it true that there were fatalities?

ANSWER: Yes, there were fatalities. I intend to detail these in my two books. What I can say for now is that, President Mugabe was told of fatalities by security organs the day he officiated his last state university graduation ceremony as Chancellor at Zimbabwe Open University during the coup on 17 November 2018. Otherwise, yes, there were fatalities and the truth will soon or later come out as it always does. Otherwise, it is not surprising that this information remains suppressed. People who to this day are suppressing the information on Gukurahundi fatalities cannot tell the truth about coup fatalities. There were fatalities on 1 August 2018 and shameless efforts were done to hide those fatalities by getting spineless medical doctors to try and falsify the cause of death from gun wounds to something else. But in the end the truth prevailed.

BSR: What do you think about the role of the regional and international community during the coup? Why didn’t anyone from the region or internationally intervene to back Mugabe when it was clear that he was being forced out by the military? Is there any truth in the claim that some regional leaders were unimpressed and would have intervened?

ANSWER: I am not sure what is meant by the assertion that no one backed President Mugabe. There were opportunities for President Mugabe to get support. Some were squandered, and others became too little, too late. I know for a fact that initially there are some leaders who offered to help as soon as the news of the coup broke out, but President Mugabe was not keen to consider that. In fact, as I indicated earlier, President Mugabe believed that the situation would be resolved internally. He was committed to that. The fact that this message of an internal resolution was conveyed, through SADC emissaries when they were in Harare on 17 November 2017 slowed things down.

Some countries, certainly within SADC, guaranteed President Mugabe’s security by letting the coup makers know, in no uncertain terms, that any harm on the President or his residence would attract a swift and stern response. Some elements among coup makers wanted to invade Blue Roof, especially on 18 November 2017 but the coup commanders new only too well that such an action would have triggered a reversal of the coup.That is why the coup announcer declared in his coup broadcast that President Mugabe was safe. So, the theory that President Mugabe was isolated is not altogether correct.

Otherwise, even going by the public record, it’s clear that Britain and China supported the coup. The immediate past British Ambassador was a coup busybody. I would not be surprised to learn that her CV now lists “toppling Mugabe who appeared invincible” as her most outstanding diplomatic feat in her career. In any event, it’s a fact that the anti-Mugabe sentiment was strong in and outside the country and the coup makers took maximum advantage of that.

BSR: You have had a fascinating and controversial political career. Before joining government, and wearing your academic hat, you were a well-known and much-admired critic of the government upon whom many people relied. These people felt betrayed when you became a vociferous defender of the Mugabe regime. Do you, when you reflect upon it now that you are outside government once again, understand why people felt this way? What would you say to them?

ANSWER: You are referring to the period when I was at the University of Zimbabwe, between 1988 and 1993. I never at that time styled myself as a government critic or an opposition politician. Being a government critic cannot be a career. I was an academic doing research and teaching undergraduate and graduate courses on electoral politics, state politics and public policy in Zimbabwe and in developing countries. Prior to that when I was a student in California, I had been an active member of Zanu PF and had served as the party’s political commissar in Los Angeles. I had also worked at the party’s offices in New York. If you revisit my record as a lecturer at UZ, you will find that I was not just a government critic, as you put, but I was public analyst critical of various public institutions including the ruling party, government as well as other public players including opposition parties, civil society, churches and international organisations.

I was critical of Zanu PF as I was of PF Zapu joining Zanu PF and I was brutally critical of Zum and Edgar Tekere as I was complimentary of Zum’s challenge to the one-party state in 1990. The same is true of my criticism of Enoch Dumbutshena’s Forum party, despite the excellent personal relationship I had with Dumbutshena whom I immensely respected. I was not a member of any political party and I did not want to be associated with any. I did not then nor would I now, as I look back, consider myself a government critic. No. I considered myself a critical academic. Full stop. I was a full time academic and I did not then dabble in partisan politics. I cherished academic freedom and distinguished it from political or civil freedoms that all human beings are entitled to regardless of their station in life. Not all human beings are entitled to academic freedom because not all of them are academics.

If as you say, as politicians or activists, people relied on my academic work in my UZ days between 1988 and 1993, that’s good news to hear but it cannot be my responsibility as to what they did with my academic work in the pursuit of their politics.My academic work was not communal or associational, it was my work as an academic and I am very proud of that work even today. That is why I have never withdrawn any of it or apologised for it. Ahead of the coup, Chiwenga publicly and shockingly cited things I wrote in my preface to my book, “The Politics of Administration in Africa” published in 1992 as evidence of my alleged treason in 2017.

Anyhow, the notion that academics should be for this or that political party as academics is repugnant and unacceptable to me. An academic cannot research or teach well, using a party manifesto. While political affiliation is like faith, in that it dictates regardless of facts, academic pursuit is not like that. Academic theories follow practice, they follow facts. And facts are stubborn.

When I joined the Constitutional Commission in 1999 and became its spokesperson, some people, I guess including those you say felt betrayed by my political choices, threw brickbats at me wanting me to boycott the Commission only and only because they were boycotting it for their own political reasons which had nothing to do with me. That offended me. I joined the Commission as an academic with practical experience in African countries that had gone through instructive constitution-making experiences. I had relevant experience which I was ready, willing and happy to offer.The draft constitution produced by the Commission was very progressive. If it had been adopted in 2000, Zimbabwe would have averted some of the calamities that have visited the nation since then. But I of course respect the fact that the people rejected that draft in a referendum.I have no regrets whatsoever about that.

And when I joined Zanu PF, a party that I had been associated with as a student, I did not do so as an academic. I did so as a human being, of course also as a Zimbabwean citizen exercising my human rights as an individual. I was making a personal decision, not a group decision. It cannot be right that you say people felt betrayed by my decision to exercise my individual rights. Freedom of association is a fundamental, inalienable and therefore natural, right that each and everyone of us is born with and thus entitled to enjoy. Significantly, freedom of association is enshrined in our Constitution.There would be no point in having this right so enshrined if its exercise requires that I consult you or anyone else to get your permission as to how I should exercise or enjoy it. For me this is fundamental. I don’t owe anyone any explanation about the exercise of my God given human rights that are constitutionally enshrined. I deal with this question extensively in my forthcoming autobiography.

BSR: An interesting feature of your career is that both your admirers and enemies have given you credit or accused you of going into ZANU PF in order to destroy it from within. Maybe “destroy from within” sounds too negative. No-one could have expected you to confirm this during your time in ZANU PF. Some think this can’t be true because without your input ZANU PF might never have survived the force of the opposition in the 2000s. Can you settle this?

ANSWER: I’m not sure that there’s an issue to settle here. But, as a matter of fact, I have never ever contemplated destroying Zanu PF from within, not least because such a mission would have been impossible as something megalomaniacally stupid in the extreme. What I wanted to do, and said as much about it on many occasions, was that I wanted to reform Zanu PF from within. I regretted that my leading role in the fight against the one-party state debate did not result in the reform of Zanu PF. Rather, it resulted in Zanu PF balking at legislating for a one-party state but becoming a de facto one-party state. I have said on many previous occasions that this happened because the one-party state debate sought to reform Zanu PF from outside its ranks. If the debate had been led from inside Zanu PF, the situation would have most probably been different. I give this only as an example of what I meant by the position that Zanu PF could only be reformed from within.

I have had to revise my view about this. Now I believe Zanu PF is inherently against reform and thus cannot be reformed from within or from outside. My view now is that Zanu PF needs to be removed and replaced in the national interests. And for the avoidance of doubt, I’m done with Zanu PF. In any event, Zanu PF is now a party of the past. The writing is on the wall.

BSR: Many people find your attitude to Mugabe and Mnangagwa confusing. You have been very critical of Mnangagwa for things that people think Mugabe was also culpable, for example Gukurahundi and corruption. Yet you have largely maintained respect and even admiration for Mugabe, while relentlessly condemning and bashing Mnangagwa. Some think this is a case of double-standards and selective outrage. What explains your approach to these two men? What is it about Mugabe that you find agreeable and about Mnangagwa that you find particularly disagreeable despite their commonalities?

ANSWER: You are indeed correct that there are these perceptions out there about my attitude toward Mugabe and Mnangagwa. I accept that this is something that I need to address. The two books I am working on address this issue, so you will have to wait a little longer, suffice to say here that, besides the primary interest to contribute to my country’s national development, a major personal reason why I joined practical politics was to understand these two men: Mugabe and Mnangagwa.

I do not agree that there are important or significant commonalities between Mugabe and Mnangagwa. The fact is that President Mugabe is a founding leader of country together with the late VP Joshua Nkomo. Founding leaders get a special dispensation. I don’t consider Mnangagwa a founding leader. I don’t put him where I put Nkomo and Mugabe. No. So the proposition that there are commonalities between Mugabe and Mnangagwa has no historical basis. I have been shocked to see the likes of Ray Ndlovu being used to write hagiographic propaganda to present Mnangagwa as a so-called decorated fighter above Mugabe, let alone Joshua Nkomo.That is utter nonsense and there’s no amount money of money that will make such nonsense true.

When it comes to Gukurahundi, the buck obviously stops with Mugabe as President or Prime Minister as the case was. That should go without saying. What I will show in my two books is that three people had terrible influence on Mugabe’s Gukurahundi disposition, one a respected foreign leader, the late Mwalimu Julius Nyerere who had issues with former Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda’s support for PF Zapu and two locals in the names of Mnangagwa and David Stannard. The worst were Mnangagwa and Stannard. They manufactured false evidence and used it to justify mass murder against Zapu and Ndebeles not only around alleged findings of arms caches but also around the creation of pseudo dissidents in collusion with apartheid South Africa.

Gukurahundi would not have occurred had Mnangagwa not conspired with Rhodesians like Stannard and apartheid operatives who were concerned about the cooperation between Zipra and Umkhonto we Sizwe to manufacture false intelligence against Zipra and PF Zapu leaders, including Joshua Nkomo. Mnangagwa created false evidence to make false history which riled Mugabe and fuelled genocide in Matabeleland and sections of the Midlands. I am not just asserting this, but these are documented facts that have failed to find expression in a truth and reconciliation process that Mnangagwa influenced to block in the old order and is still blocking in the so-called new dispensation. If Mnangagwa is as innocent as he is portrayed in Ray Ndlovu’s shocking hagiography, let him publish the Chihambakwe report on gukurahundi. That would be a significant development and a confirmation that there’s indeed a new dispensation.

So, as the person who presided over the creation of the false evidence that was used to justify the military and CIO operations, including the establishment of the Fifth Brigade, against PF Zapu and Ndebeles, Mnangagwa should own up, take ownership pf that false evidence, and apologise.

You joined politics from the academic and research world. What would you tell young academic and researchers who hope to transition into politics? What advice would you give to so-called technocrats who have recently joined government with the hope of making a difference? What are the pitfalls and opportunities?

ANSWER: As a political scientist, I take the locus classicus view that everyone is a zoon politikon. As human beings, we are all political animals. Politics is what distinguishes human beings from other species. As such, in the political realm, there’s nothing special about academics and researchers. Politics is associational, it is about communal life. It is in this connection that the best politics is local. Everyone has a local address somewhere on a street, at some village or location of one sort or another. To enter politics means becoming relevant to a local community somewhere, and normally this means where you live, where you work or where you were born or where you come from.

Young academics must understand this as the relevant and most important starting point of politics. Anything else is a waste of time. It does not make sense to want to get into politics simply on account of being an academic, a researcher or a technocrat under the presumption of getting into so-called national politics.Again, there’s no one with a national address, everyone has a local address and that is where politics starts and thrives.

In the same vein, young academics and researchers should understand that politics is about providing solutions to public policy issues that affect people in specific localities or communities. Ideally, skilled or experienced people with the knowhow to proffer practical solutions to practical problems are academics, researchers and entrepreneurs or business people.

The so-called technocrats who have recently joined government should appreciate that there are no technocrats in cabinet, the central committee or the politburo. There are no technocrats in politics. Only the civil service has technocrats, not cabinet. Everyone in cabinet is a politician, the rule book of cabinet is political. Specifically, the claim that the likes of Mthuli Ncube and Kirsty Coventry are technocrats is nonsense. They may have been that yesterday, but today they are politicians just like the rest of their colleagues. And their success or failure will depend on how they perform as politicians, not as technocrats.

Besides, politicians in Zimbabwe who join politics as technocrats should know that established political parties cannot stand intellectuals or entrepreneurs.Anyone believed to be knowledgeable or with useable information is considered very dangerous. Technocrats typically work hard over long hours in their offices.This is a no, no in party politics. If you do that, you invite claims that you are ambitious and must be closely observed to be kept in check and stopped dead in your tracks.

Based on my personal experience, I do not recommend that young people in academia and research should entertain ideas of transitioning into party politics. One of the major deficits of public discourse in Zimbabwe is the absence of researched and independent opinions and solutions from academia. The last 20 or so years have seen political noise from partisan academics while most academics have remained silent under the false presumption that the political arena is not theirs but for politicians. That’s wrong. Politics is for everyone. Party politics is but one form of politics, and not necessarily the best form. I would urge young academics and researchers to be vocal and to participate in public debates as academics and researchers not only to provide practical solutions to practical problems but also to keep partisan politicians in check.

BSR: Finally, do you think there will be another coup in Zimbabwe? Why?

ANSWER: The possibility of another military coup in Zimbabwe is a real, clear and present Sword of Damocles that has been menacingly hanging over the country since November 2017. This is because coups invariably beget one another. Zimbabwe will remain in a coup zone until the 2017 coup is cured. The fact that those who led the coup are in power means that there are no prospects of curing the coup in the current scheme of things. The only path to any change in Zimbabwe today is via a military coup or a military-assisted transition.

It is unfortunate, and a very serious indictment of the country’s state politics, that 38 years after independence and five years after adopting a people-driven democratic Constitution Zimbabwe is a military state as a direct result of a military coup.To cure this outside a military coup would require a thorough-going and radical realignment of the balance of forces led by visionary, brave and courageous new generational leaders.Any other proposition is non-starter.

I am encouraged by the fact that there is a visible clash of generations in the country. I see the emergence of a younger generation, which is in the majority and which is also well represented in the military, that is dead set against military rule and its politics of entitlement. The values of Zimbabwe’s new millennials, whom I have described as Generation 40, are antithetical to the values of the nationalist old guard behind the November 2017 coup. The old guard in Zimbabwe is anti-modern, tribal, uneducated, anti-progress, irrational and driven by primitive beliefs such as witchcraft and the like. While it is an issue today, military rule has no future in Zimbabwe. Those who are staking their political careers and business fortunes on military rule in the country are banking on quicksand.

BSR: Thank you very much Professor Moyo for taking time to have this important conversation with us. Thank you also for your kind words about the BSR. At the BSR we often analyse what key political actors would have said and done. But we thought it would be a good idea to get it from the horse’s mouth, so to speak. I would like to think there will be more opportunities for similar conversations as there is much to speak about. Some readers might say we should have discussed other issues, but this specific occasion was to discuss the events of last November, which we commemorate this month. We will use this opportunity to say the door is open to other actors as we generate this series of “Conversations”. Finally, we wish you all the best with your two books which we hope will add the pot of ideas and thoughts regarding the politics of our nation.