HARARE – Veteran Zimbabwe opposition legislator Joel Gabbuza thought he was stating the obvious when he told mourners that President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s ruling Zanu PF party was struggling to revive the economy.

Gabbuza, who has been representing the impoverished Binga South constituency for over a decade, was arrested for lamenting the fuel shortages that brought the country to a standstill a month ago.

However, in a move that took human rights activists by surprise, the MP was charged with “undermining the authority of or insulting the president”.

Prosecutors said the legislator told villagers that President Mnangagwa’s government was clueless in solving Zimbabwe’s economic problems that have, of late, spawned shortages of fuel and medicines.

Crush dissent

When he appeared in court on November 12, prosecutors said Gabbuza of the Movement for Democratic Alliance told mourners he had been forced to travel to neighbouring Zambia to source fuel for use during the funeral.

The notorious piece of legislation under which the legislator is being charged– Section 33 (2)(b) of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) – was routinely used by former Zimbabwe strongman Robert Mugabe to crush dissent.

In November last year when the 94-year-old leader was toppled in a coup and was replaced by Mnangagwa, there was optimism that such repressive legislation would be immediately repealed.

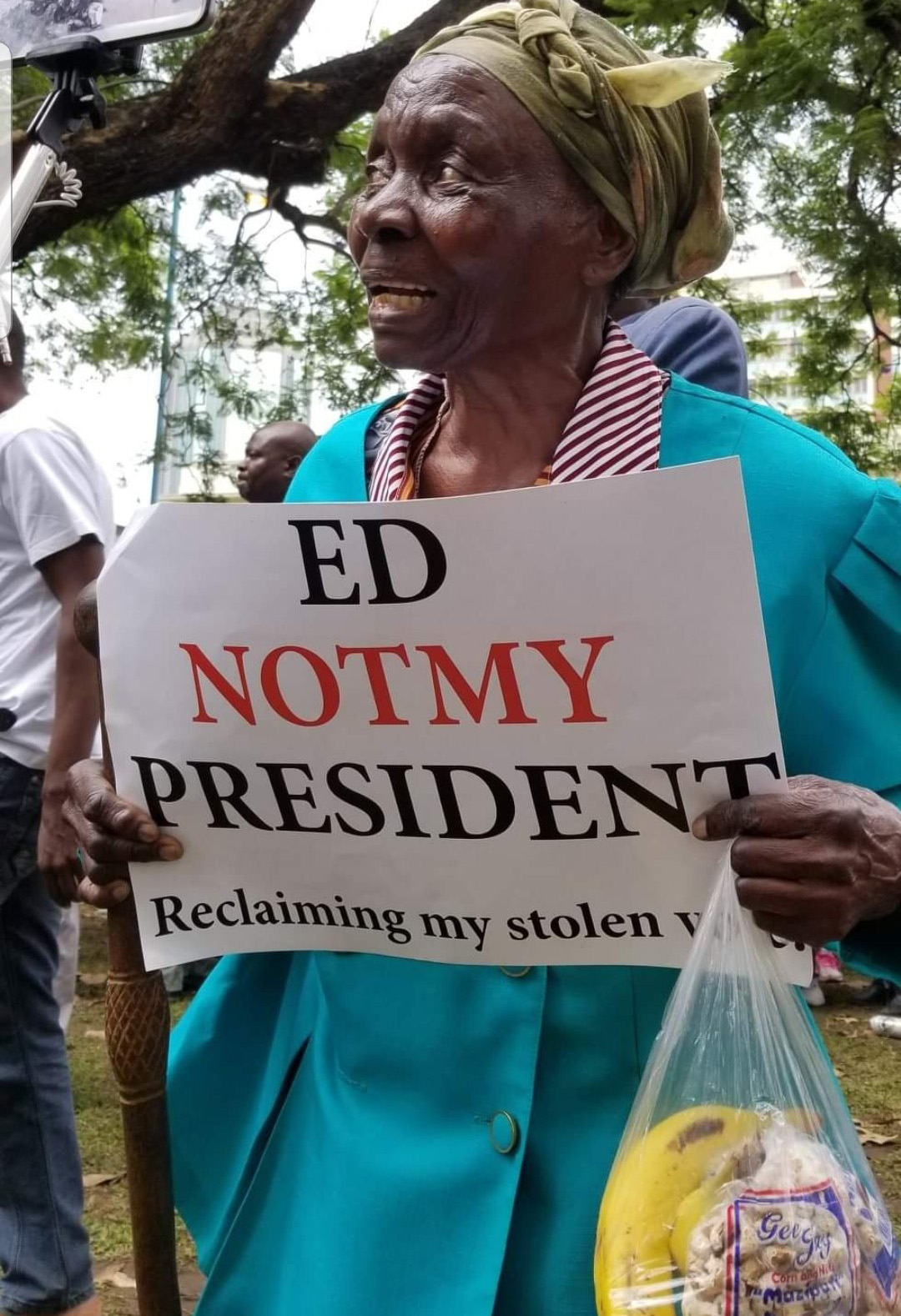

The new president, a long-time confidante of Mugabe, had promised a ‘new dawn’ where there would be freedom of speech, but a year after the historic transition, Gabbuza’s case is an apt indication that little has changed in Zimbabwe.

The insult laws

According to the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR), at least 10 people have been charged with insulting the president or undermining the office of the president since November last year.

“From 2010 to the end of his rule last year, Mugabe’s government had arrested over 200 citizens and charged them under the notorious insult laws,” said ZLHR spokesperson Kumbirai Mafunda.

One of the biggest victims of the insult laws in President Mnangagwa’s one year in power is John Mahlabera, a prison officer, who early last month lost his job after referring to opposition leader Nelson Chamisa as his president.

Mahlabera was charged for using Twitter to declare his loyalty to Chamisa on the eve of the disputed July 30 elections. He was accused of using “traitorous or disloyal words regarding the leader of government”.

On the other hand, Gabbuza faces at least 20 years in jail if he is convicted on the charges of insulting the president.

South Africa-based human rights lawyer Siphosami Malunga believes nothing much has changed in Zimbabwe under President Mnangagwa because the same people who propped up his predecessor were still in charge.

Malunga, who is also the executive director of the Open Society for Southern Africa, said the manner in which Mugabe was overthrown did not set the right tone for a fresh start for a country that was under a dictatorship for three decades.

“I did not want the soldiers who removed him to take over from Mugabe,” the renowned lawyer wrote in an opinion article commemorating the first anniversary of the coup and titled; Lost opportunity: How Zimbabwe missed a chance for change.

“I wanted them to retreat to the barracks and continue protecting the country as they had done very well for years,” Malunga added.

“I did not want them in politics. I wanted many of Mugabe’s close comrades to go with him to allow for a fresh start.”

Ministerial posts

Former Zimbabwe national army commander General (Rtd) Constantino Chiwenga, who led the November 14 coup, became vice-president in the post Mugabe government.

The commander of the Airforce Perrance Shiri and another top general Sibusiso Moyo, who announced the coup through the national broadcaster, were rewarded with senior ministerial posts.

Opposition leaders and civil society say the former generals are part of the hardliners that allegedly manipulated the July 30 elections where President Mnangagwa beat Chamisa with a small margin.

The army is also accused of deploying soldiers who shot dead six protestors in Harare on August 1 as tensions rose over delays in the announcement of the presidential election results.

Malunga believes Zimbabweans should have insisted on a transitional government that would have spearheaded major reforms and discarded repressive laws.

Major opportunity

“The rapture of the constitution created an opportunity for the people to reconfigure the governance arrangement of the country post-Mugabe,” he said.

“They could have remained on the streets as a key player pushing for the reforms they desired no-matter what the risk was.

“They could have demanded an inclusive transitional government arrangement to lead the country through the interregnum and democratic restoration.

“Had that happened, the country’s trajectory could have been very different. So a major opportunity was lost.”

UK-based constitutional expert Alex Magaisa said although Mugabe’s ouster was largely welcomed, the coup was a reversal for the democratisation of the country.

“The removal of Mugabe must be regarded as a landmark moment in our history, not only because it ended a long and influential political career, but also because, and more importantly altered the constitutional order and whose implications will be felt for generations to come,” he said.

“If people thought that was unimportant, the events of August 1, 2018 (the killing of protestors by the army), two days after the election, are a stark reminder of the critical significance of that precedent (coup).”

Magaisa, a former advisor to late ex-prime minister Morgan Tsvangirai, said the coup would haunt Zimbabwe for some time as it remained a threat to the country’s stability.

“Much has happened since the coup and, while it was good to see Mugabe leave, I remain concerned by the impact of the coup on the country’s constitutional order and that another may happen again, especially because the last was given a veneer of legality,” he added.

Besides, lack of reforms to enhance freedom of expression and association as well as reducing political tensions, Mugabe’s ouster has not resulted in a swift economic revival that many hoped for.

Instead, prices of basic commodities and medicines have gone up by more than five times since November last year.

In the last two months, the country has witnessed severe foreign currency shortages that resulted in fuel supplies drying up and empty supermarket shelves.

Decades of decline

But former opposition legislator Eddie Cross argues that Mnangagwa is on course to transform the economy and end two decades of decline.

Cross, an economist, said the new president had already demonstrated that he was different from Mugabe.

“The emphasis of ‘being open for business and the start made in returning to the international playing field has elicited considerable private sector interest and I personally have a list of private sector projects that, if implemented, will involve the investment of $30 billion and will generate many billions in new exports and hundreds of thousands of new jobs,” he said.

“This was impossible under Mugabe.”

Cross said the economic problems that seemed to be worsening could not be compared to those witnessed under the former president’s rule.

In 2009 Zimbabwe abandoned its inflation-ravaged currency and people lost their lifetime savings.

Growing rapidly

“I now hear people saying that the resumption of shortages and fuel queues and the sudden emergence of a parallel market for hard currencies means that we are going back into the conditions we experienced in 2005 to 2008,” he said.

“Nothing could be further from the truth, our economic fundamentals are sound, exports and the GDP are growing rapidly and once the new team in the Ministry of Finance started to tackle the macro economic problems of the country, they were immediately rewarded by a sharp reduction in the fiscal deficit and we will be in surplus by Christmas.”

Cross added: “At this pace we will be in a different country by March 2019.”

One of Mnangagwa’s high profile appointments in the post-election government was that of former African Development Bank vice-president Mthuli Ncube.

Prof Ncube, who holds a PhD in Mathematical Finance from Cambridge University, is the new Finance minister and has put in place austerity measures to tackle a government deficit and reboot the economy.