HARARE – The Zimbabwe government could shut down in the next 14 days after a representative body of its 300,000 employees gave notice of a nationwide strike.

The Apex Council, which represents all public sector workers, said Tuesday that “despite numerous meetings being held between the government and staff associations” for improved pay, “there has not been any tangible results to date.”

Doctors have been on strike for over a month and teachers embarked on an indefinite strike starting on Monday. They are demanding to be paid in United States dollars, or alternatively they want their salaries paid in RTGS to be adjusted to match the prevailing cost of living.

The government has committed to review the salaries of its employees, but without providing a timeline.

“The Apex Council representing the entire civil service hereby serve notice of collective job action within the next 14 days from the date of this letter,” the body’s president Cecilia Alexander said in a statement.

“The reason for this step is premised on the incapacitation of our members and the failure by government to address the same. The incapacitation comes in the wake of the erosion of our static salaries due to the sky rocketing cost of living.”

The strike, whose form was not outlined, could see the entire government bureaucracy come to a halt.

The Zimbabwe government is a patronage machine of astonishing scale, with 300,000 employees whose wages alone eat up almost 90 percent of the country’s tax revenue.

In 2009, when a power sharing government between former President Robert Mugabe and the late MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai first dollarized, the total wage bill was around US$30 million per month, according to the Information Ministry. Now the salaries bill is $300 million per month.

Almost every economic prescription for Zimbabwe, though, starts with the dual-currency conundrum, and the potential fixes are unpalatable. According to RBZ governor John Mangudya, in November last year the country’s commercial banks held about $10 billion in deposits, “of which only 4,5 percent are coins and notes, which is your bond notes and coins.” It also includes about $50 million in hard currency.

Restoring the bond note to true parity with the U.S. dollar probably would require a huge injection of capital, for which there is no clear source.

The World Bank and International Monetary Fund won’t lend to Zimbabwe because the country is in arrears on past financing. No private investors are apparent. A U.S. bailout is out of question over the little matter of sanctions imposed on Zimbabwe’s leaders; and China’s foreign-investment priorities are biased toward hard infrastructure that provides work for its companies—not shovelling funds into what could be a black hole.

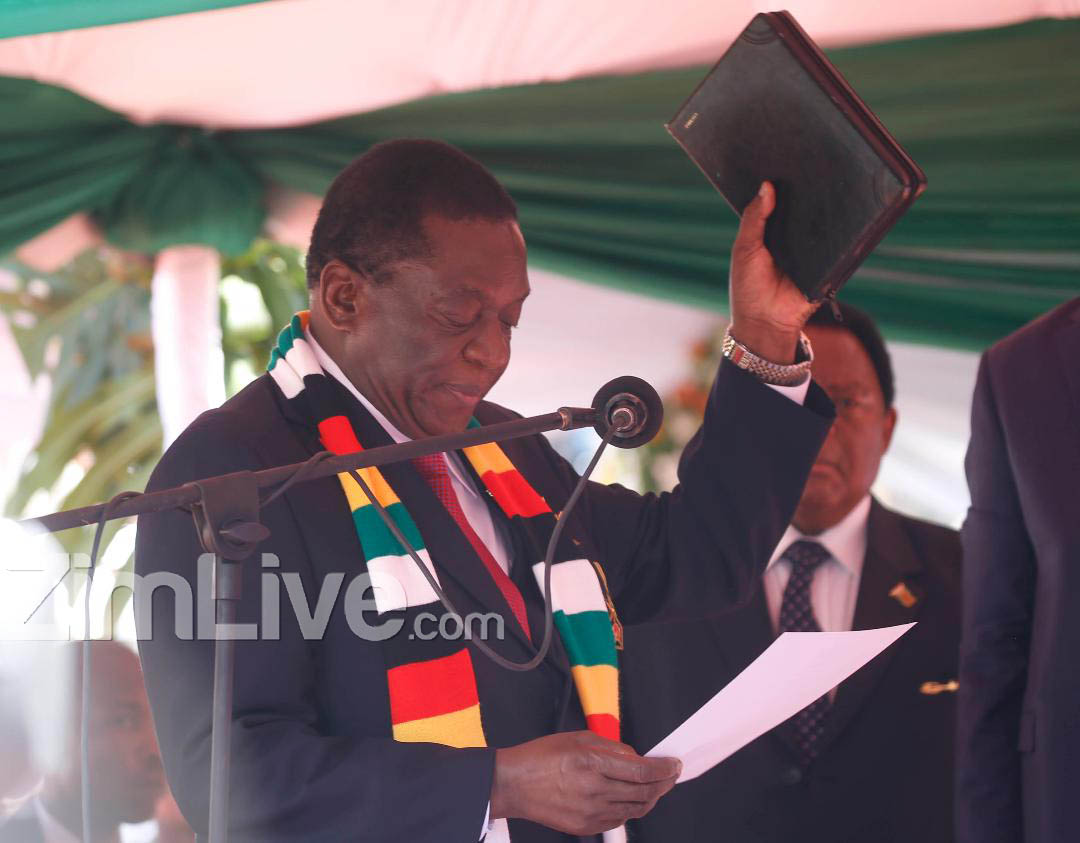

The crisis has left President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s government virtually cornered. In its 2019 budget, the government did not budget for salary increases for its employees and any ambitions finance minister Mthuli Ncube might have had of getting a handle on the fiscal deficit have gone up in smoke.

The MDC’s former finance minister Tendai Biti says “the solution is to re-dollarize the economy and remove the bond note… The solution is to seek dialogue with MDC”. But Zanu PF so far appears intent on going solo as it weathers the coming storm.

Additional reporting by Bloomberg