ON Fathers’ Day which also happened to be Youth Day or Soweto Uprising Day in South Africa, I sat to talk to my two children Naledi and Mondliwethu about many “important” things. They rolled their eyes up as if to say “not again” when I said “let me tell you about my father and his father. You all can say what you want about me as your father if you want when I am gone.”

My grandfather worked in the gold mines in Filabusi all his life. I wonder how much gold he personally brought up from that still thriving gold mine. He died poor for a gold miner, coughing and wheezing – I am most convinced now, likely from silicosis – although it was not diagnosed as that at the time.

He had three children. My father the only son, and according to my aunt (his sister), got the only ticket to go to school. My father would of course remind us at every opportunity that he walked barefoot for almost 20km to school and back everyday whenever we asked for bus fare to get to school about 5km from our home in Fourwinds. We too – his kids – would roll our eyes up on these fancy and unnecessary tales of a man obsessed with bombarding us about his past suffering with which we had nothing to do.

In time, my father had graduated well enough to be admitted to the main teacher training institute at Empandeni Mission. Choices were limited for black intelligentsia. It was either you became a teacher or a nurse in the mid-1950s. It was a generational leap from miner and my grandfather was immensely proud of his achievements. In his mind, he had bequeathed opportunity to the next generation.

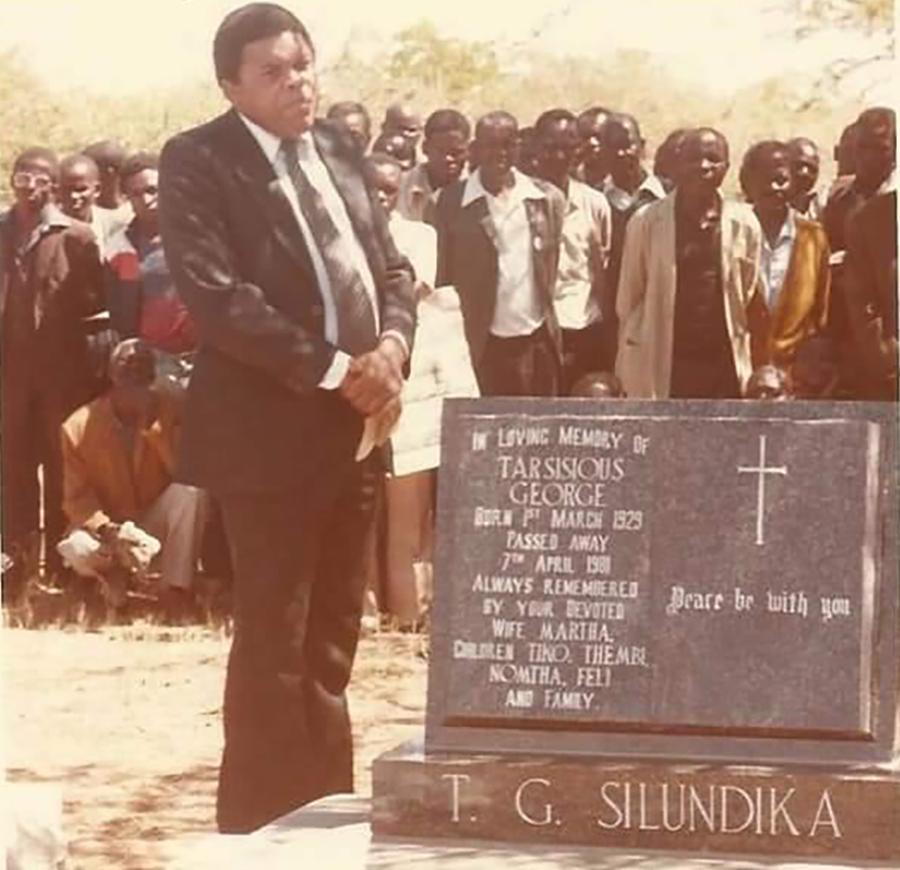

My father’s stars would lead him to the nationalists George Silundika (TG) and Robert Mugabe who taught at Empandeni Mission. TG became his teacher and mentor and introduced him to politics. He would graduate and do more politics than teaching and together with his mentor quickly find his way to Smith’s prison – but not before meeting my mother who was pursuing the only available professional option black women could at the time – nursing – at Fatima Mission. Only when they got to prison, would the nationalists pursue further study with UNISA.

My father would spend more time in prison than outside it. I calculated with sadness as I spoke to my children that, post-independence he only spent eight years outside prison as a free man. I was 23-years-old when he died, in my last year of law school. Law had never been my first choice. I wanted to be an air force pilot. I had broken this news to him in the kitchen after writing my Ordinary Level exams in 1988. His reaction shocked me. I got a slap, was told I would do my Advanced Level and study something serious like law. That was it. No further discussion.

So, whilst my father never got to see the lawyer me, I imagine he felt proud of his own achievements in bequeathing to his children opportunities that had been denied him.

Our talk ended with Fanon. My 20-year-son has read “Black Skin, White Masks” but not “The Wretched of the Earth.” I quickly Googled and read out Fanon’s “each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.” We “agreed” we are all reading “Wretched of the Earth”, especially my 15-year-old daughter Naledi who has not yet read Fanon and seemed excited. She is a reader!

One generation can only do so much. With whatever it has. My grandfather’s generation did its part as did my father’s. Many are quick to “weaponise the legacy of heroic icons against their children” – I learnt this term recently as I followed the Zindzi Mandela controversy where she has taken on the land issue – notwithstanding using “strong and undiplomatic” language. She is being accused by some of betraying her father’s reconciliatory spirit. What nonsense!

Every generation must be judged on its own circumstances. But do something it must. That was my message to my children on Soweto Uprising/Fathers Day.

*Siphosami Malunga writes in his personal capacity