WASHINGTON – Zimbabwe is creating a straw-man by blaming sanctions for the lack of investment and a failing economy, a top official with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) says.

Jason Taylor, the director of USAID’s Humanitarian Assistance and Resilience office in Zimbabwe, said the southern African country had simply failed to convince investors that their investments would be safe.

Taylor spoke during a discussion on “Zimbabwe’s burgeoning food crisis” in Washington D.C. after listening to President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s economic adviser Ashok Chakravarti, who argued that the targeted U.S. sanctions created a “perception risk”.

The United States passed the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (ZIDERA) in 2001 in response to human rights violations and land seizures targeting white farmers. The sanctions targeted listed individuals and entities accused of aiding the violations.

ZIDERA also directs United States citizens who sit on the boards of multilateral financial institutions to vote against any loans and debt cancellations for Zimbabwe.

“You’re right to say that ZIDERA exists, it’s also true to say that it has never been implemented,” Taylor told Chakravarti during a May 1 panel discussion hosted by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

“ZIDERA only comes into effect when Zimbabwe clears all its arrears to international financial institutions. That’s the point at which discussion about ZIDERA can begin. And so the idea that ZIDERA is ruining the investment climate in Zimbabwe is simply not true.

“Regarding the other sanctions, about 82 individuals who have been sanctioned, about 56 institutions have sanctions, these are individual targeted sanctions. So, there’s nothing in ZIDERA, nor is there anything in the targeted sanctions that prohibits investment in Zimbabwe.

“I would argue what prohibits investment is a lack of economic reform, a lack of property rights, a lack of a secure investment climate and lack of a political and human rights context that businesses appreciate. I think to point to sanctions is to create a straw-man and destroy that straw-man and do nothing about the root causes that you are addressing.”

Chakravarti recounted a personal story about how a transfer of $4,000 to his daughter studying in the U.S. was blocked by the Office of Foreign Assets Control, a U.S. Treasury Department financial and intelligence agency that administers and enforces U.S. sanctions.

“Because the correspondent bank saw Zimbabwe written over there, it blocked this transfer for her fees. I have all the papers… You think that ZIDERA doesn’t make a difference; some years ago we had about 40 banks which dealt with Zimbabwe. It’s a fact that there are only about a half-a-dozen correspondent banks that are willing to deal with Zimbabwe now because of the perceived risk,” Chakravarti argued.

U.S State Department Deputy Assistant Secretary for Africa, Matthew Harrington, who also spoke at the event, said the positive image that the Zimbabwean government projected to Western capitals as it sought legitimacy and international acceptance following a military coup in 2017 and subsequent elections disputed by the opposition last year had all but disappeared thanks to sustained human rights violations and failure by President Emmerson Mnangagwa to embrace basic political reforms.

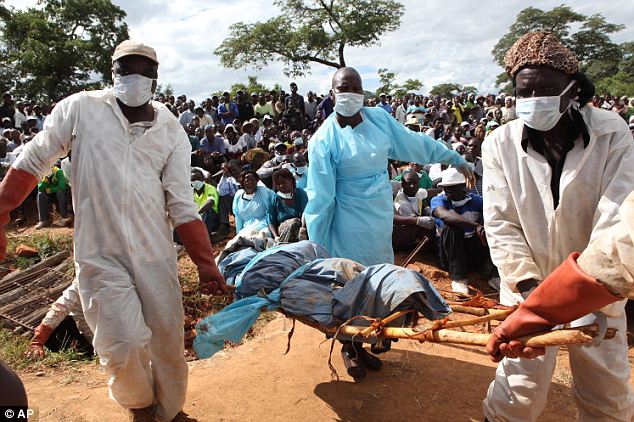

Citing the killing of civilians, including women and children by security forces in the wake of nationwide protests over fuel price increases in January and “several [other] problematic developments,” Harrington said Mnangagwa and his Zanu PF government have not demonstrated any willingness to change and set Zimbabwe on a trajectory that promotes the rule of law and democratic principles.

“The success of Zimbabwe’s economic reforms is inextricably linked to the implementation of profound political change, and we’re not seeing much progress on the latter. The government is saying some of the right things, but it is falling short when it comes to concrete actions,” Harrington said.

The revised ZIDERA of 2018 lays out the reforms needed for Zimbabwe to have a normalised relationship with the United States.

“Those include restoration of the rule of law, an equitable and transparent land reform process and a military and police force that are subordinate to the civilian government. We welcome a better relationship with Zimbabwe, but the ball is very much in the government of Zimbabwe’s court. If there is real, concrete progress in the areas laid out in the ZIDERA legislation, Zimbabwe will find a committed partner in the United States,” Harrington added.