LUPANE – Elections come and go, but there is a fraction of Gukurahundi survivors and victims who are continuously denied their fundamental rights to participate in elections, access healthcare as well as political and economic inclusion because they lack national identity documents.

“I have never had an identity document that identifies me as a Zimbabwean citizen, which allows me to vote and elect the leaders I want to be in office,” said 56-year-old Zodwa Sibanda from Lupane’s Jibajiba village.

Sibanda vividly recalls her father being tortured and burnt alive while she and her three siblings stood helplessly watching a horrendous event that would scar them for life.

She attempted to obtain identity credentials after the Gukurahundi murders but was unsuccessful because she did not meet the civil registration standards.

“It’s a heartbreaking experience to be a Gukurahundi survivor. The lack of identity documents serves as a constant reminder of the traumatising memories I endured as a child.

“I feel like our government has let me and other victims with no identity documents down. I have not received any public apology, compensation, and there have been no efforts to ensure that we are treated like citizens with dignity,” added Sibanda.

Sibanda is a widow with two children, Steven and Melusi, who left the country seeking greener pastures in South Africa in 2005 and 2007 respectively. She has not been in contact with them since they left, as she lacks a cell phone and their contact information.

Gukurahundi and its contribution to statelessness

Gukurahundi was a politically motivated genocide which took place between 1982 and 1987, during Zimbabwe’s post-independence political upheaval. It marked the bloodiest period since independence.

Soldiers from the North-Korean trained Fifth Brigade were deployed in Matabeleland North, Matabeleland South and Midlands province with instructions to quell dissidents, following the discovery of an alleged arms cache, which former president Robert Mugabe’s administration said belonged to Zipra, Zapu’s armed wing during the liberation struggle.

Zapu was led by Joshua Nkomo.

Several Zapu and former Zipra leaders among them Dumiso Dabengwa and Lookout Masuku, were arrested in the crackdown and charged with treason.

The treason allegations were found baseless by the courts, hundreds of some Zipra defected to the bush in disillusionment, over the crackdown, which claimed the lives of thousands of civilians.

Although there are disagreements over the number of people killed during the massacres, the Catholic Commission on Justice and Peace (CCJP) claims that over 20,000 lives were lost during the Gukurahundi atrocities.

On December 22, 1987, after years of Fifth Brigade-induced carnage and misery, Mugabe and Nkomo reached a political pact to cease the conflict, after the signing of the Unity Accord which merged the two political parties.

The Unity Accord ended bloodshed, but a genuine national peace and reconciliation process which addressed the victims’ grievances or gave them support for the trauma they endured was not put in place.

Government did not institute special measures to ensure the issuance of death certificates for people killed in the Gukurahundi operation.

As a result, those orphaned had no means to prove their parents’ nationality and were therefore unable to acquire identity documents. They were therefore left as stateless people.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2020 report estimates that at least 300 000 people in Zimbabwe are at risk of statelessness.

Discussions over Gukurahundi atrocities are still being discussed in hushed tones in many parts of Matabeleland South, Midlands and Matabeleland North despite pressure from some chiefs, pressure groups and civil society organisations which have been demanding justice for victims.

Despite the government’s recent efforts to assist vulnerable groups in obtaining identity documents through a nationwide registration programme launched last year, the devastating impact of Gukurahundi survivors not being able to obtain identity documents continues to be a recurring generational phenomenon.

This is owing to the Registrar General’s (RG) office’s stringent criteria for parents’ and guardians’ identity documents and death certificates as prerequisites for accessing birth certificates and identity cards.

However, because parents and guardians lack identity documents, many children have also found it difficult to access the vital documents.

We can’t vote: Gukurahundi victims

An investigation by ZimLive in collaboration with Information for Development Trust (IDT) under a project probing corruption, bad governance and electoral manipulation, revealed that some Gukurahundi victims and survivors devised plans over the years to adopt their paternal or maternal distant relatives surnames in order to access national identity documents. Many of those who did not resort to such desperate measures have remained stateless.

When President Emmerson Mnangagwa took office, he pledged that his administration would establish a meaningful national and healing process for Gukurahundi victims.

The Mnangagwa administration assigned traditional chiefs from Matabeleland provinces to take the lead in settling disputes.

Traditional authorities have however, made little progress in initiating a true national healing process and supporting Gukurahundi victims in obtaining identity documents.

This is due to a multitude of issues, including traditional leaders’ lack of resources and suspected state agents bullying and pressuring victims into not publicly testifying about their ordeal.

Ndodana Ndlovu, a 40-year-old unemployed villager from Mpofu village in Lupane, whose father was killed during Gukurahundi lamented how his failure to access an ID had resulted in him being unable to vote, get employment and access healthcare.

Ndlovu had previously obtained a national identity card using a flawed birth certificate, which documented that he and his younger brother Mduduzi, were born the same year, but in separate months.

When Ndlovu lost his national identity nearly a decade ago, he sought a replacement, but the civil registry department discovered anomalies in his and his siblings’ documented dates of birth. He was denied a new identity document.

The civil registry advised Ndlovu to come back with his brother, whom he hasn’t seen or communicated with since he left for Botswana decades ago.

“I have lost hope of acquiring a national identification document, participating in elections, being formally employed or accessing health services,” Ndlovu says.

Ndlovu’s mother who took his and siblings birth certificates is deceased.

The birth date irregularities were the result of a chaotic civil registration effort conducted shortly after the Gukurahundi horrors.

Several people who received identification documents in the late 1980s and early 1990s acknowledged that they had similar birth dates anomalies being experienced by Ndlovu.

Ndlovu is surviving on informal jobs to fend for his family as he is unable to be formally employed because of the lack of a national identity card.

“It now bothers me that my children will face the same difficulty in obtaining national identity documents and, as a result, will struggle in life,” he says.

“I survive on piece jobs to support my family, which is not easy to come by, and would love to have a national identity card so that I can seek formal employment and vote for the leaders I want.

“I will not be able to vote like everyone else, with an identity card, on 23 August.”

Gukurahundi victims and survivors that spoke to this publication on and off record highlighted a myriad of challenges of not possessing national identity documents and the hostilities they faced from RG office whenever they tried to acquire the documents.

“Government’s promises to assist us get national identity documents has all been talk and less action. We also want the right to vote and elect leaders of our choice.

“Since the Gukurahundi atrocities, we have been treated as second-class citizens, excluded from development issues.

“As we speak in Lupane, there are many business opportunities, including timber, that benefit people from outside Lupane. This is not fair,” said a Lupane Gukurahundi victim who requested anonymity.

Observations on the field in Lupane and Tsholotsho were that many Gukurahundi victims were not willing to open up in fear of victimization.

There is a heavy presence of state agents and the Central Intelligence Organisation run shadowy group Forever Associates Zimbabwe (Faz) which is mobilizing votes for Zanu PF ahead of the polls.

Faz members have been intimidating and discouraging Gukurahundi victims from speaking or sharing their painful experiences regarded as anti-government.

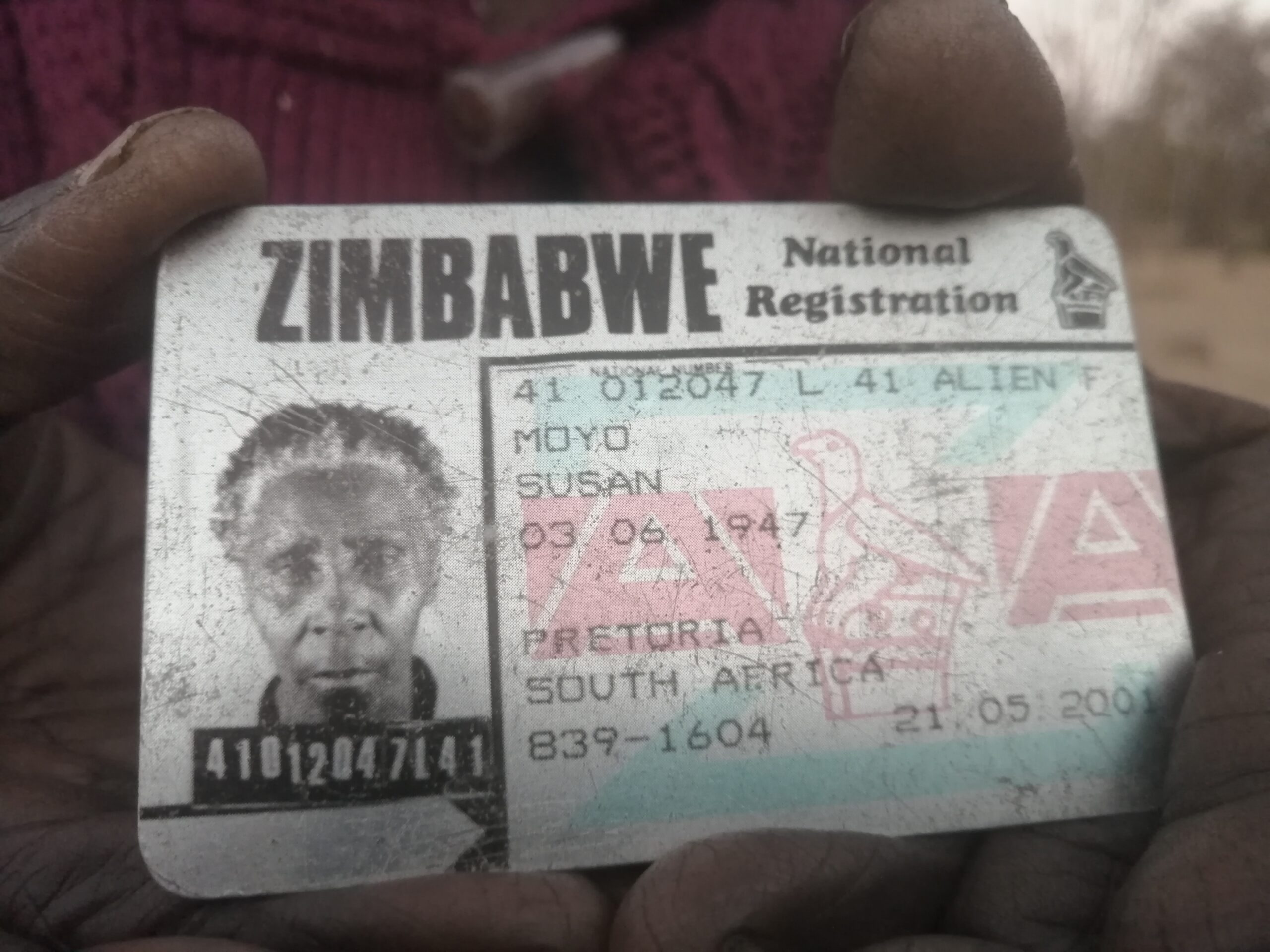

Some of the Gukurahundi survivors were able to access national identity cards with their actual ages altered and some written alien.

Susan Moyo, a Gukurahundi survivor from Mpofu Village in Lupane whose husband was killed during the Gukurahundi massacres, lamented that her national identity card identifies her as alien and has made it impossible for her to vote.

Citizens, who have national identity cards that identify them as aliens that were issued before the 2013 constitution, are not permitted to vote unless and until they regularize their identity cards with the Registrar General’s offices.

The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) during the March voter blitz that concurrently with the national registration blitz encouraged citizens with identity documents that identify them as aliens to regularize with the RG’s office to be availed the opportunity to vote.

Moyo however said her attempts to regularise her identity document have so far been unsuccessful.

“I live in Lupane, and my husband was killed during Gukurahundi in Tsholotsho, when he was kidnapped by soldiers and fatally shot by the river. We were compelled to take cover in the bushes,” she said.

“Right now, I am not allowed to vote because the current national identification card I have identifies me as an alien of South African origin.

“At the civil registry, they refused to regularise my national identification number after several attempts and they demanded money, which I do not have; where will I get the money if I do not work.

“I want to vote for my leaders of choice but am unable to because my national identification card lists me as an alien,” said Moyo.

The problem of stateless citizens is widespread in Matabeleland: community organisations.

Rural Communities Empowerment Trust (Rucet) coordinator Vumani Ndlovu in an interview said restrictions faced by Gukuruhundi victims were a multifaceted generational conundrum.

He urged government to come up with measures to assist all victims to receive identity documents.

“There are many people in rural Lupane, Nkayi, and Tsholotsho who do not have national IDs or birth certificates; the first challenge stems from the fact that access to identification documentation is centralized in growth point centers,” Ndlovu said.

“However, the majority of people who do not have identification documents come from wards that are more than 100 kilometers from registration centers, so people in remote areas face a significant challenge.

“Another critical issue is the Gukurahundi (massacres), which have affected generations and generations of people accessing national ids, that is, if the father was killed before taking identity cards for his children, his grandchildren will not be able to access national ids.”

Ndlovu said as a result of economic challenges and the failure to get documents Matabeleland had witnessed a high rate of migration to neighbouring South Africa, Botswana, and Zambia.

“Because not having a national ID prevents them from accessing social services, healthcare, and education. We are urging the government to take into account the needs of persons of such caliber (victims) in obtaining identification documents,” added Vumani Ndlovu.

A survey by this reporter in Ndamuleni, Silwane, and Jibajiba villages in Lupane confirmed some people lacked national identity documents. Some were however afraid to testify fearing that this reporter was part of the Faz team.

Ibhetshu LikaZulu co-ordinator Mbuso Fuzwayo, said there is need for the government to change its rigid policies that have deprived Gukurahundi victims from accessing national identity documents and participating in elections.

“I have been to Tsholotsho, Nkayi, Matopo and Gwanda.

“The areas I have gone through there are people who are complaining that as the country is going for elections, they are not going to exercise their citizens’ rights because they do not have documentation to reflect that their parents died during Gukurahundi,” Fuzwayo said.

“The government says that people can access (identification documents) but whilst they are saying that, they do not change the system and manner with which it’s done, so those people did not access the documentation and will not be able to vote.”

In August 2019, President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration announced that it would issue birth and death certificates with immediate effect.

Government also said it would process and roll out medical payouts for those who were injured in the Gukurahundi massacres.

However, the birth and death certificates have not been issued by Mnangagwa’s government as promised, meaning election participation and access to healthcare for victims without identity documents remains a pipe dream.

Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission (ZHRC) from March 2019 to March 2020 conducted a national inquiry that produced a plethora of recommendations intended to ease the issuance of national identity documents to the Gukurahundi victims.

The ZHRC report concluded that Gukurahundi victims’ access to identity documentation had impeded their rights to enjoy constitutionally ascribed rights and that there was a need for imperative action for the RG to ensure victims obtained identity documents.

Highlighting the grievances of being stateless the ZHRC report outlined the systematic impediments by the RG’s office which had exacerbated Gukurahundi victims failing to access documents which needed to be neutralised.

ZHRC’s report also recorded detailed lived experiences and testimonies of affected people, which clearly illustrated the myriad of challenges confronting victims’ plight to access documentation and the impact thereof on their lives.

Despite recommendations adjudicated by ZHRC the RG’s office has been reluctant to amend and relax its requirements to ensure Gukurahundi survivors obtain identity documents.

Another recent report by ZHRC stated that approximately 90 percent of the Gukurahundi survivors were suffering from mental impairments caused by trauma.

Recommendations made by the ZHRC have, however, not been successfully implemented.

ZHRC chairperson Elasto Hilarious Mugwadi in an interview said the commission was convinced that government’s nationwide civil registration exercise had cushioned the problems faced by Gukurahundi victims in accessing identity documentation.

He said the commission would investigate further, the recurring problem of victims failing to access identity documents.

“Reference is made to the issues you raised in respect of the problems being faced by survivors of the Gukurahundi onslaught in accessing vital National Documentation.

“My commission will take steps to further investigate the nature of the problems and make recommendations to the Registrar General’s office,” Mugwadi said.

“The intention of the National Inquiry as you well know was to ensure that no one and no place was left behind in accessing the fundamental human rights and freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights of the Constitution in accordance with the adopted mantra of the second administration.”

A Gukurahundi survivor from Matobo, who preferred anonymity, bemoaned how the failure to obtain a national identity document had deterred him from exercising his constitutional rights.

“My parents were killed when I was two years old, and I don’t have any identity documents to do anything productive with my life right now,” he said.

“I have always wanted to vote for leadership that I believe has the best developmental manifesto that would gratify me if given the opportunity, but I am unable to do so because I lack a national identity document.

“I have tried approaching the RG’s offices to explain my situation, but without my parents’ death certificates and my own birth certificate, my matter always falls on deaf ears.”

Julia Ndimande, a Lupane villager, who is a Gukurahundi survivor in an interview shared a success story how she was able to obtain identity cards of her nephews and nieces whose parents were killed during the Gukurahundi atrocities.

“I faced challenges accessing birth certificates for my two late brothers’ children who were killed during Gukurahundi because I did not meet the civil registry requirements of availing death certificates to confirm the parentage of the children.

“At the local registry they refused to give me the death certificates after I explained that they were killed during Gukurahundi.

“I was finally assisted by social services at Tredgold, Bulawayo, who facilitated that I get the death certificates to be able to assist my brothers’ children obtain identity documents.

Attempts to obtain a response from the civil registry and the RG’s office were futile. Shingirai Nyandoro from the civil registry public relations department directed questions to the Registrar General Henry Tawona Machiri who did not respond to the calls and messages sent to him.

Obert Gutu, the spokesperson for the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC), said he was too “busy” to respond to the questions sent to him.

Many victims are however not in a position to travel to Bulawayo for assistance largely because of the lack of knowledge and financial resources of how to overcome the numerous obstacles on their way.