JOHANNESBURG, South Africa – Let me tell you a story. It’s a story I tell because I am sad, angry and hopeless. A story of grief. Often when I feel this way, I write to numb the pain.

It’s the story of Patricia Majalisa and the story of Dalom Music, my home away from home for more than 20 years.

But it’s more a Patricia Majalisa story today. I don’t know anyone who has endured so much heartache and heartbreak all her life. I didn’t speak to Patricia Majalisa all the time. But when we spoke, it would be a long catch up session, punctuated by pain, laughter and nostalgia.

The irony of her sudden death is that whenever there was a death in the music industry, especially from our era in the 80s/90s South African disco/pop period, she would be the first to let me know.

The task to tell me she’s no more has now fallen on someone else’s lap.

In the 90s and early 2000s, I met many artists at her houses in Yeoville and Bellview. Through her I met the country’s first gay band, 3Sum, Amstel, Jeff and Koyo, when I pulled up to see her, unannounced. I was the first journalist to profile this band when nobody could give them a minute of their time. Only Amstel is still alive.

I met Maxwell Mlilo, who was in Emzini Wezinsizwa before he was Captain Shai in Yizo Yizo. He even lived in her house after his divorce. He died years ago.

Artists thought I was Patricia’s relative. Until she introduced me. When you’re a young man from Bulawayo, artists like Patricia Majalisa and Dan Tshanda are gods. When you meet them in the flesh in your 20s, and you eat in their homes and drive with them, it’s an experience you can’t describe.

When I pitched stories at Drum, I had to find very unique angles for the stories to get approval from the powers that be in Cape Town. When I arrived at Drum I got a rude awakening: very few gave a damn about most of the South African artists I worshipped, from Peta Teanet, Ray Phiri, Pat Shange, Joe Shirimane, Freddie Gwala to Dan Tshanda.

The attitude was the same everywhere else. I remember a photographer laughing when I told him we were going to interview Joe Shirimane.

You only read about these artists of yesteryear when they died poor or if they ran foul of the law. I made it my mission to write about them while they were still alive. Sometimes, I won. This usually meant spending a lot of time with these artists, away from the recording studio, traveling with them, to get a solid angle. And that’s how I got to know Patricia Majalisa so well. Sometimes we laughed through tragedy, together.

She was hijacked outside her house years ago. She told me the criminals drove with her towards Vereeniging, forcing her to lie on someone’s lap as they demanded her bank card pin. She was driving out to go to the shops when they pounced.It happened so quickly she didn’t realise what had happened until she could feel the cold barrel of a gun on her cheek.

She couldn’t remember the pin code so they drove around with her hoping she would calm down and remember. She couldn’t. Then one of the scumbags recognised her. He told the other three and they asked her to sing her popular songs for her freedom. She didn’t remember the lyrics. She was weeping and asking them to take the car and spare her.

They let her sit up and started singing her songs for her. She felt much better. Then they dropped her off. She was able to get a lift back home. When she went to the police station, she couldn’t remember her car registration number. The car was never found.

We have laughed about this incident over the years, but she said something that made my heart stop: “If I wasn’t Patricia Majalisa, I would probably have died that day.”

I know that Patricia was going through a lot in the last few years. No longer the Majalisa of yesteryear. There’s nothing heartbreaking than an icon like her telling you she’s sitting in the dark because she has run out of electricity. But because I know her very well, and I know how life is for most of our icons from her era, I understood what she was going through. I learnt for the first time this year how to buy electricity on the FNB app because of Patricia.

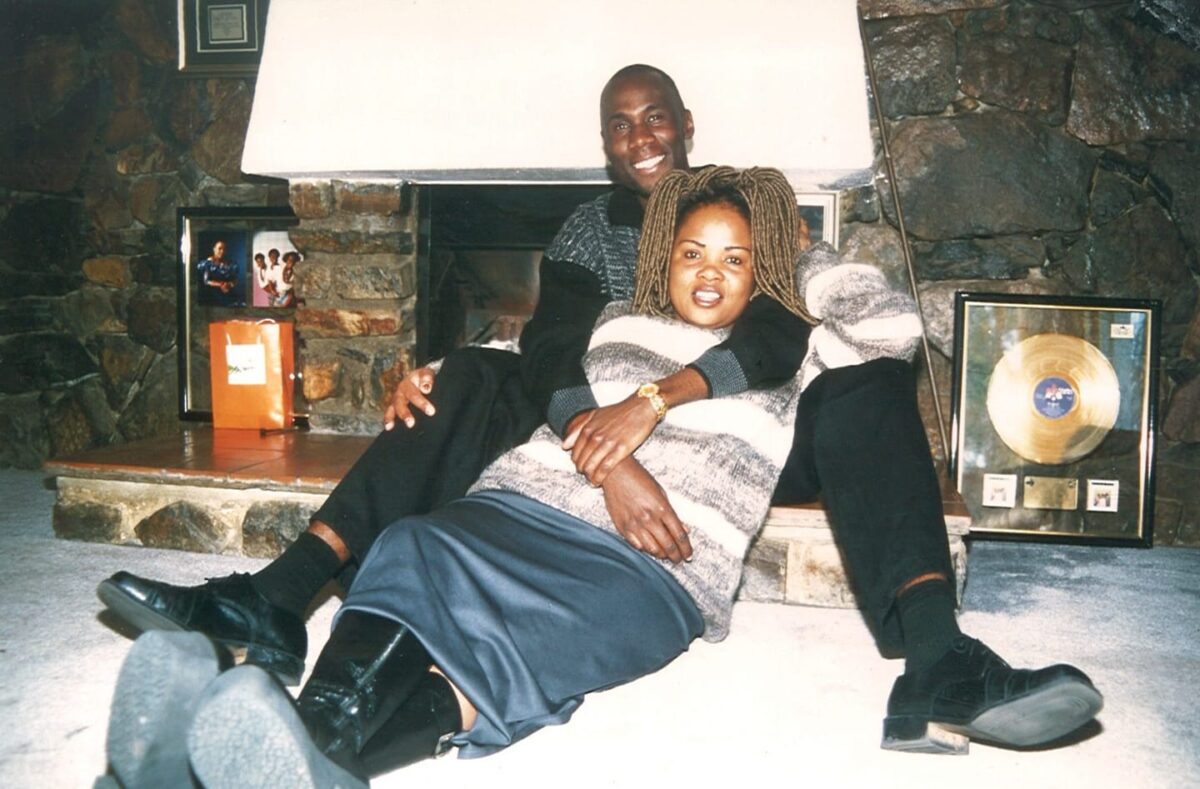

We spoke about everything. I know how much she still loved Dan and how devastating his death was to her, how she never recovered from their breakup many, many years ago. She was shattered by his untimely death, and never accepted or recovered from it. None of us, his friends, have come to terms with Tshanda’s death.

Matshikos’s song We Miss You, was a tribute to the late great Joseph Tshimange, the first to depart. But now I find I have played it each time the rest of them left us. Today I sing it for my friend Patricia Majalisa.

She avoided talking about Dan and refused all efforts I made for her to return to Dalom Music. It’s a deep, deep story of love, friendship, youth, money, jealous, betrayal and revenge.

“You can’t undo what was done, Japhet,” she insisted.

But I kept trying till the end.

I had reached out to Dan’s widow to bring together all former Dalom artists alive to continue the work her husband did. Then Covid-19 happened and we didn’t meet.

I know the Dalom story very well and have told it during my younger years as a Drum journalist. The tragic story brought me even closer to artists like Majalisa, Dan, Penwell Kunene and Thabile Mazolwana, the young man from the Eastern Cape known as Peacock, whose debut album I witnessed being recorded. He is sadly also gone.

If there’s anything I loved Dan for, it was his honesty and openness when I asked difficult questions, including what happened between him and Patricia, between him and Joseph Tshimange, between him and Penwell Kunene (he didn’t even attend the funeral and I demanded answers), and between him and Patronella Rampou, our other friend whose funeral in Carletonville I covered on a cold winter morning in June 2001 (Drum, June7, 2001).

Dan didn’t attend that funeral either. I was there. Only one member of Dalom Kids pitched. It was the saddest thing I have ever witnessed. She too died broken-hearted, alone, broke, deserted and bitter, leaving behind her lovely boy, Lesego.

She died just 10 months after photographer Johnny Onverwacht and I had been to see her in August of 2000. She was pursuing gospel music to sooth the pain. The headline for my story summed it all up: “Buried with a broken heart”. A story of a woman who wept for her lost love right to the end. It’s the worst thing to see someone slip away and you can’t do anything about it. It stays with you forever. That interview haunts me to this day.

Her son was at school and she insisted we wait for him so they could both appear in the magazine (Drum.31 August 2000). We obliged. There’s a picture on the page of them together, smiling, sitting on a blue leather couch. A mother and son moment to behold. It would be the last time I saw her alive. I haven’t seen Lesego since the funeral.

I must say this, for the record, because it is important: for all the stories I wrote about artists in his stable, Dan Tshanda gave me total access to them and allowed them to tell their stories, sometimes allowing me to interview them at his home or studio. He never tried to stop me from writing anything. Until he died, we were still great friends. In fact, when I went to his house in Wendywood after writing a story I thought he wouldn’t like, he opened the doors for me and made me listen to music that wasn’t yet released.

For the first time in his career, he was comfortable with a journalist doing a story about his mansion, his family and the things that kept him awake at night. Throughout the interview, he told me to listen to lyrics of specific songs, like Danny, Snake, Jealousy, Luvhengo, Money, Ndoneta and Vhobhalelwa. They told his side of the story, and answered most of the questions. I didn’t listen to the songs at the time. But as years went by and I did another interview with someone from that stable, the pieces of the Dalom puzzle came together.

When we spoke, Dan would say something really deep, then ask me if I listened to this or that song. “Some of those songs come from a place of pain,” he said, fighting back the tears. “Sometimes people don’t know what you’re going through.” Indeed.

The Dalom story is tragic for me. That’s what happens when you get too close to a story. When artists become friends, and become family. The final chapter of the story, for me personally, is today. Patricia Majalisa is the final installment. The end.

Last week my best friend Eric Knight asked me to go and interview Patricia Majalisa for his newly established online radio station, Radio54 African Panorama, which he runs out of Manchester, UK. It was to run with the launch of the station on Monday. I couldn’t say no because we come a long way together, him as a top broadcaster in Harare in the early 90s, and when I was wet behind the ears and trying to stay alive in a cruel world.

Last week, I asked Patricia if I could come see her, but she said she couldn’t see me. She couldn’t tell me why she wouldn’t see. She has always been available to see me.

Eric then suggested I do Yvonne Chaka Chaka. But that, too, didn’t happen. Yvonne said we can do Monday, the day the station would launch. Then she postponed again.

Today, I get a text message from Bonisile Ndlovu, a mutual friend and former Dalom Kids member. “Just letting you know that mama is dead Patricia Majalisa.” I froze. I called Boni and she couldn’t even talk. She’s in tears. Devastated. I know how close they were. Pat was like a mother to her. Boni knows the whole story, all the secrets Patricia is taking with her to the grave. They were inseparable from the Dalom years when I met both and told their stories. They’re all finished now. Gone. My dear friends.

Joseph Tshimange. Gone.

Penwell Kunene. Gone.

Daniel Tshanda. Gone.

And now Patricia Majalisa. Gone.

The original Splash. The original Matshikos.

Gone.

These were my friends. They’re all gone now. I don’t have anymore tears. Just heartache. Questions. No answers.

If heaven does really exist, I hope there’s a reunion going on right now. I know we will be very lucky if any of the local press give her space on their pages, so this is my personal tribute to a fallen soldier, an icon, a friend.

I know Twitter and Facebook will be quiet, too, because like a prophet, Patricia Majalisa was big and appreciated far away from home. Botswana, particularly, almost single-handedly kept Dalom artists fed. They were royalty there. They still are.

Condolences to the Majalisa family, the Dalom Music family and all close friends and fans of her music. This is devastating. Rest in peace dear friend.

Japhet Ncube is editor of The Star newspaper in South Africa