Transcript of a public lecture by human rights advocate Siphosami Malunga delivered on Independence Day on April 18, 2023

IT IS indeed an honor and a privilege to be asked to deliver this lecture on this auspicious occasion of our independence. Independence is a very important day for Zimbabweans; it symbolises a very important break with a very terrible and tortured past, and it is quite important that we reflect, on this Independence Day, on the journey we have travelled.

I have been asked to deliver a lecture on whether the struggle was really worth it. This is a loaded question. I have tried to break it into manageable pieces that may help us navigate this tough, difficult question. I have no doubt that people have different opinions about this issue, and I will just offer mine, hopefully as an input into a much wider conversation on this issue.

I guess we might start off by asking ourselves this question: “Why was the liberation struggle necessary?” The majority of our population right now was born after independence; we need to contend with the reality that a person who was born in 1980 is now 43 years old and has very little reflection of the liberation struggle. They are 43 years old, which therefore means that they didn’t experience it, and if we take the demographics of Zimbabwe, as with many other African countries, over 75 percent of the population is below the age of 35, and the median age is 19.

What does that really mean? It means that most of the people who have to hear about, discuss, or reflect on the liberation struggle never experienced it. Some of us were young at the time; with the aid of other historical experiences, we may contribute a little bit about “why was it really necessary?” and some of us, our fathers were key actors and players in the liberation struggle, and we can reflect on what we believe from their accounts drove them to the liberation struggle.

We need to start off where it really starts, lest we forget. Lest we forget, Rhodesia was a terrible place for black people. I know that when people struggle with day-to-day issues in life like water, energy, power, education, food, transportation, and bad roads, they often say Rhodesia was better, but let us put everything in context. Rhodesia was a very terrible place for black people, in every way imaginable. Ian Smith put in place a racist minority regime that was oppressive, exclusive, very destructive, exploitative, predatory, corrupt, and abusive, largely abusive of black people. So, I will unpack this regime called Rhodesia because we have to talk about what Rhodesia was in order to unpack the necessity of the liberation struggle, and then we will move on to talk about whether, at the end of the liberation struggle, what it purported to deliver was delivered and whether it was therefore worth it. That is the journey that I will try to take.

The colonial regime was racist because it was entirely composed of white people, who made up less than three or four percent of the population, and it excluded a majority of black people from any meaningful participation in the politics, economy, and social life of the country.

It was oppressive because it used discriminatory laws, institutions, and practices to abuse and oppress black people and privilege white people. It was exclusive because it implemented structural segregation much like apartheid in South Africa, which favoured the white minority over the black majority.

It was destructive; it destroyed our traditional way of life, our culture, our systems of governance, coexistence, our way of life, our mighty kingdoms and chieftainship, relationships, and livelihoods, and replaced all these with imported religion. It reconfigured our societal, political, social, and economic relationships through divide and rule strategies in order to conquer both the people and the territory of Zimbabwe, and the whole fundamental intention was to create out of us a labour reserve for the white Rhodesian agricultural and extractive economies.

That is what Rhodesia did — it destroyed what it found. It needed to destroy what it found in order to replace it with this settler-colonial state where we were labourers, offering cheap labour for the maximum benefit of the white minority.

It was exploitative. It was exploitative because it abused and forcibly took advantage of black bodies, black labour, black assets, black knowledge, black land, black capital, and our culture, as I have already alluded to. It was also predatory because, in everything it did, it was aimed at serving the sole interests of the white minority at the expense of the black majority.

It was corrupt. Many may not understand or know the levels of corruption that were in Rhodesia because we contend that corruption still exists in day-to-day life in Zimbabwe. Why was it corrupt? It was immoral, and it abused its public power for the political, social, and economic benefit of the small group and minority. It was also abusive because it deployed laws, public institutions, and officials to abuse and violate the political, economic, and social rights of the majority black population.

Racist, oppressive, exploitative, exclusive, predatory, destructive, abusive, and corrupt—that was Rhodesia, and this sets the background for you as to whether and why it was necessary to wage a liberation struggle against this system that I have just described here. So, the question is: was the armed liberation struggle inevitable or justified? Rhodesia was the reason for and the rushing out of the liberation struggle. The Rhodesia that I have just described to you as oppressive, exploitative, exclusive, predatory, destructive, abusive, and corrupt was the reason for the liberation struggle.

We must not forget that the establishment and consolidation of the racist system combined a cocktail of strategies, including religious deceit. Of course, we know they sent Robert Moffat and the missionaries to try to deceive our Kings and our Chiefs. Religious deceit, trickery, and violence are how the Rhodesian state was established. Its maintenance required violence and coercion because, obviously, people would never accept being oppressed, so you needed another strategy to maintain it. So, in that process, violence and coercion combined the use of oppressive laws, institutions, and violence systems aimed at upholding white supremacy and maintaining black oppression in their own country over their own resources over their own land, and of course inevitably violence begets violence.

The armed liberation struggle was a legitimate response to a violent and oppressive system, a legitimate response recognised by the world as self-determination, and a legitimate response to the deployment of violence to fight against a violent and oppressive colonial system, which was endorsed and supported by the international community as part of the decolonisation agenda. In law, as I am a lawyer, I like to refer to it as “just war” or “the right to resort to war,” or what we sometimes call “jus ad bellum” in Latin. So, the reality is that the liberation struggle was a choiceless response to an oppressive, violent, and predatory system that left the black person little choice but to fight back, which the black person did. So, it culminated in what we call independence.

Was the liberation struggle worth it? When you measure the worth of something, you just calculate the cost of doing it versus the gain that you get from doing it. If the cost is too high and the gains are too low, it’s not worth it. If the price is too high, it’s not worth it. As we reflect and measure, we should also appreciate that the measurement and choice are made at a point by people who might not have been at the place of measuring necessity. We must always recognise that. When you measure wealth over 43 years or maybe 50 because this liberation struggle began years ago, we are looking at the 1970s, the late 1960s, so the people who were measuring necessity and worth are different from us who are now measuring worth.

We must also accept that fallibility in these kinds of scrutiny and questions that we ask ourselves: the people who were making those calls at the time were making those calls based on their own realities. So somebody could argue this is an academic debate, but the reality is that if people fight to achieve something, the question is whether it has been achieved after they fought for it, so we must and we are entitled to ask that question, “Was it worth it?”

The answer to dealing with the question of worth starts with looking at where we are on the issues that drove and underpinned the liberation struggle. Looking back, we look at what proponents and actors of the liberation struggle claimed to be fighting for. The things that they wanted to remove and eradicate, where are we on those issues? That is the way in which we could assess whether it was worth it. We will of course dwell on the necessities because we know that the Rhodesian system was undemocratic, exploitative, discriminatory, abusive, oppressive, coercive, and violent. We also know that it left no choice to those at the time that had to contend with it but to fight it back, and they fought it back with everything they had, but was it worth it?

I spoke about looking at the cost; what is it that you got out of it? What went into the liberation struggle was huge sacrifice — lives, time, and pain — not just by those who went in the liberation struggle that went across the boarders to mobilise an armed struggle by the entire nation.

We must never forget, and I have said this before, that we have had to be fair and rule out that certain people—only a certain group of people—liberated Zimbabwe. That is far from the truth. Zimbabweans as a whole liberated Zimbabwe, they lifted and carried the burden of resisting Rhodesia. They carried the risk of protecting and supporting the freedom fighters. Our people suffered immensely under Rhodesia, and our people, the Zimbabweans, fought back against Rhodesia. If it was ZIPRA and ZANLA alone; they would never have succeeded were it not for the amazing, unbelievable, and selfless sacrifice of the people of Zimbabwe.

Many were killed, many were jailed, many suffered. Only a few days ago, this past weekend, my Chief, Chief Dambisamahubo Mafu, who is the heir to Chief Vezi Maduna, who was a close friend of my father and who grew up with him in Filabusi, was installed. I was reflecting because I spent almost the whole day with Chief Maduna before he died. He had summoned me to talk to me about a number of things that I will share one day; I think I might have shared them at some point. I remember him telling me that he had been in 10 different Rhodesian jails. He was a chief, a descendant of Godlwayo the Chief, Mzilikazi’s general. He spent time under Rhodesia in 10 different jails. So, the reality is that the Rhodesians left the blacks with no choice; of course, they had to fight, and they fought. The fundamental question you must ask is, “Did that deliver anything?” What did it deliver?

Rhodesia denied the black person dignity, self-worth, basic treatment, a decent opportunity to earn a livelihood of his choice, respect, quality of life, education, health, water, sanitation, and energy. I know that now because we have rolling power cuts in Zimbabwe, our roads are in shambles, and we don’t have water. We sometimes forget that there was water for white people and water for black people in Rhodesia. There were roads for white people and roads for black people. There were houses for white people and houses for black people. The houses that were built for black people were small, on small pieces of land, with small bedrooms. Many families were supposed to stay in those tiny spaces of land. The houses they built for white people had big yards for their dogs. They had swimming pools and all the space for lanes, trees, and gardens, but we must remember that it was the unequal treatment between blacks and whites in a country that belonged to blacks that drove people to fight back for their dignity.

Rhodesia paid black people different wages from white people doing the same jobs, if black people were even lucky to do the same job. It was impossible for a black person to become a lawyer, a doctor, or an engineer. The most you could become was what my mother became: a nurse; what my father became: a teacher; and then, of course, a liberation fighter. We must not forget this about Rhodesia; it stole our dignity and the dignity of our people. It robbed us of the quality of life and the life we chose. It moved people to villages where there was no rain or water. It turned people who were industrious into labourers on farms who worked for peanuts or nothing on white farms. We must not forget this.

These are the issues that drove the liberation struggle fighters to go and fight. We must not forget that other issues that drove and underpinned the liberation struggle included the use of the state in abusing the laws and the institutions all there to keep black people down, to oppress, to stop them from voicing an opinion, organising themselves politically, or going to certain places. You could not stay when you went to visit emayadini, where the white people lived, because you used different toilets. You could not access different parts of the city, certain stores, so the institutionalised structural racist segregatory system drove people to fight against it to create an equal system for everybody, a system in which you could use any toilet if you needed to, a system in which you could live anywhere, in which you could live in a house as big as you wished, in a system in which you could be an entrepreneur, you didn’t need to only sell your labour, and if you had the capability, you could pursue any profession of your choice.

I became a lawyer; my father wanted to be a lawyer but could not be one, and he was adamant that I was going to become a lawyer because he also understood the importance of law in his life as he battled the Rhodesian legal system and oppressive laws of Rhodesia as he spent many, many years in prison; he could never be a lawyer himself at the time.

The other thing that drove the struggle, which we need to look at and weigh between then and now, is the predatory elite. It has been established, as I said earlier, that the Rhodesian elite was predatory, and I explained why it was predatory. It sought to benefit itself, the minority, at the expense of the black majority. Every decision, every law, every institution, every policy was calculated to deprive and discriminate against the blacks and advantage and privileging the whites. It was predatory. There was no policy that was made without predation as a motive. At some point we will go back to these issues and look at where we are as Zimbabweans.

A discriminatory political, economic, and social system underpinned Rhodesia and was very discriminatory in everything you did, including the school you went to: if you were black, you couldn’t go to a white school. The teachers in a white school were better trained than those in black schools. The facilities were better; the quality of the schools better: look at Milton High School and Gifford High School. Everything was different for blacks and whites politically; if you were black, you had no place in participating. You could not be a councillor, you could not be a member of parliament, you could not be anything really. Socially, where you lived, where you played, and where you went for entertainment were all very critical.

Exploitation: the black people fought against it. The black people felt exploited by the white minority. They felt that their land was exploited because it was taken, and they were moved from places where they stayed – think of the Land Apportionment Act, the Land Tenure Act. These laws were created to reinforce these unequal and discriminatory commercial and economic practices that seek to entrench white superiority and black inferiority.

The Rhodesian regime was exploitative: it used the state’s power to exploit, to take from the majority black people, and to give to the minority white people. It exploited black labour for low wages. Dangerous labour, it didn’t matter; safety was not crucial and important. I know this for a fact because I have spoken about this in a meeting of parliamentarians some years back: my grandfather was a miner, and he used to go down the mine at Fredda Rebecca Mine in Filabusi. I don’t know how many times he went down there. I don’t know how much gold he brought up from the mine. He died poor; he didn’t even have an ounce of gold, but I’m sure in his life he carried a lot of gold. He died coughing, sneezing, and wheezing, and I believe he died from these diseases that miners got. Many of the miners in Gauteng have had it. Nobody cared about the safety of those miners and farmers; it was a case of maximising profits.

The life of the black person was immaterial; the life of the black was exploitative. It was oppressive. I’ve already talked about this. We will measure all these criticisms against where we are currently in Zimbabwe.

It was exclusive; it excluded blacks from many professions, many areas, many geographic spaces, and many opportunities; and it was corrupt; it was devoid of any ethical, moral authority, any integrity, and any persuasion of any sort. It was unaccountable to the majority of the people over whom it overloaded. We must ask ourselves the question, “Was it worth it?” Was the liberation struggle worth it? Where do we stand? Where do we stand on the dignity and self-worth of the citizens of Zimbabwe? What is the score card for basic decent treatment, livelihood, respect for human beings, and quality of life? Where do we stand on this? Education, health, water, energy, and sanitation Where do we stand?

I ask these questions in a rhetorical way and in a rhetorical manner for you to answer because you know where we stand. You know that the life of a black man in Zimbabwe is no valuable now than it was under Rhodesia. We know that the black person struggles for a meal, struggles for water to drink, struggles for electricity, and struggles to access health care, regardless of what we may be told in propaganda. We know for certain that if you fall ill now with a serious illness, your likelihood of dying is 99.9 percent because you will not find even paracetamol in hospitals. We know this to be true.

We know that the quality of teachers that was terrible for the black population is terrible now for everybody because teachers are not paid and are not valued. We know the dilapidation of our schools in the provision of education material. We know that it’s rare for you to open a tap and clean water comes out; if it comes out, it is filthy, dirty, poisonous, and dangerous to consume.

We know that you can no longer have sustained periods of power connections; on the contrary, you have days, sometimes weeks, of no electricity. This is what we know is prevailing right now. Was it worth it?

Looking at the contemporary situation in Zimbabwe and what our forebearers sought to change, was it worth it? We are also clear, my father was clear: we fought to change the system. The institutions were coercive, the officials were discriminatory, we fought against this, the state was instrumentalised against the people, and that was Rhodesia. The state fought to protect minority interests against the majority. What is the state of affairs now? In whose interest does the Zimbabwean state operate?

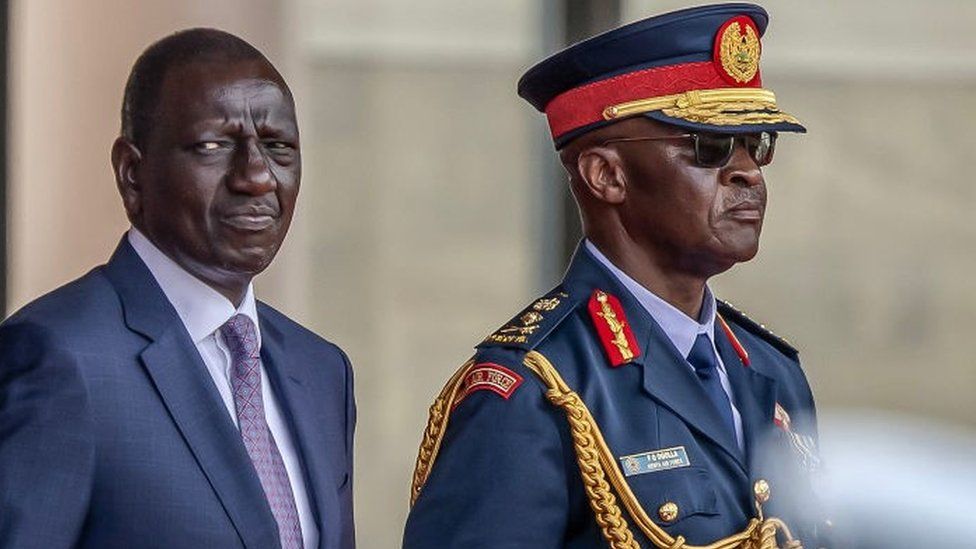

I will talk about the similarities between Rhodesia and Zimbabwe. Where are we? The reality is that little might have changed in the way in which a state might be configured or in the way in which the state postures itself. The same laws with different amendments and configurations are used to stop people from expressing themselves and demanding their God-given rights to speak. The very clarion call of the movement was democracy. We want to determine our future. We want black people to vote. One man, one vote. We want to have a say in our government, yet we have the same suppression of votes, the same suppression of the black person from speaking, from demanding, from participating in the political life of his own liberated country. We have elites again, like in Rhodesia, but it is the black elite that is simply doing the same things that instrumentalise the state as coercive and violent.

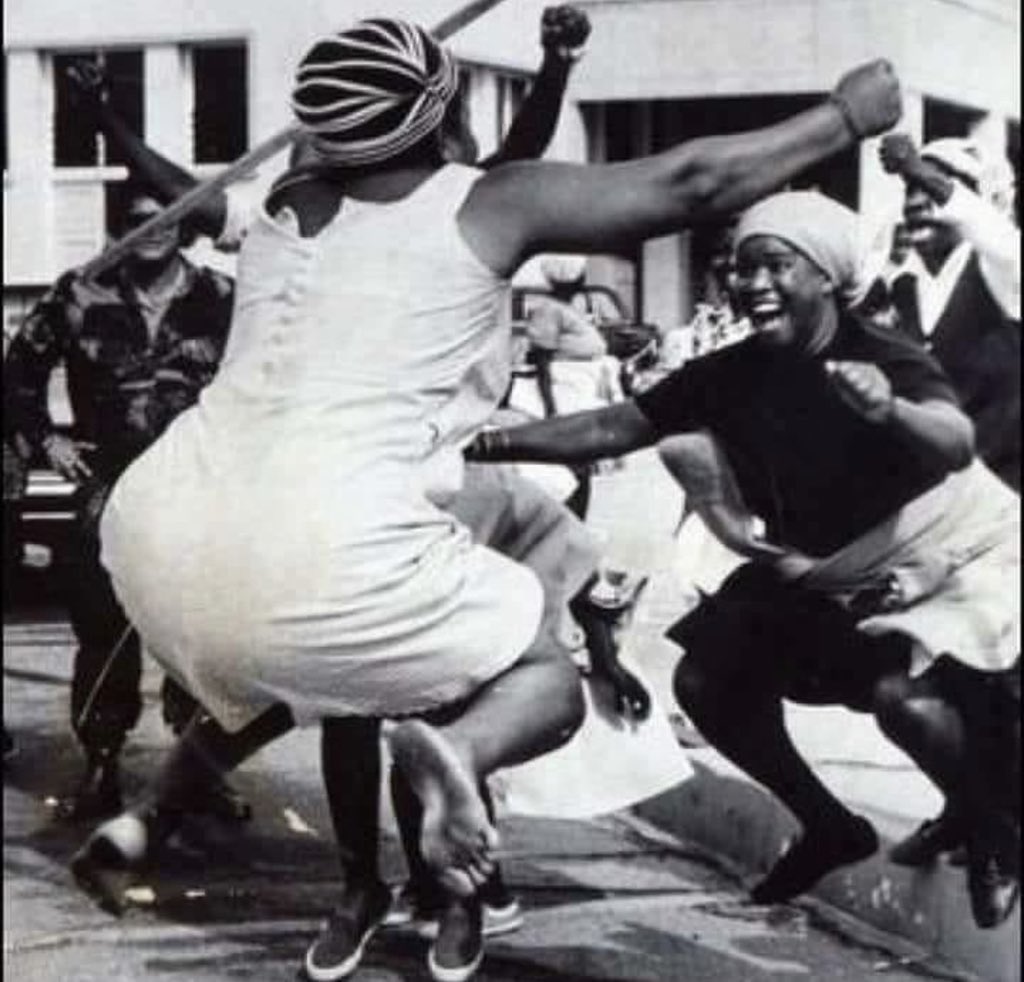

Where do we stand? Was it worth it? Because if it was, perhaps we would not be having the same kind of system as Rhodesia. Why is violence so pervasive? Violence was the first and primary instinct of the Rhodesian government. It deployed violence in the most efficient way, which is why our fathers decided that it was pointless to talk to the Rhodesians and say, “Please listen to us, let us share, give us a chance to participate.” They realised that whenever you did that, you were thrown in jail and tortured; therefore, they deployed the same language that was deployed against them. Hence the liberation struggle. Was it worth it?

I will come to the conclusion that it has not delivered on the liberation promises given the realities that we have the same system of governance, the same script, oppressive laws, policies, institutions, and the pervasive use of violence to maintain and retain the political system run by a small elite that continues to exploit and benefit from the whole state for its own personal gain.

Was it worth it? This is the question I ask and must conclude, and of course we have a different take on this. Some people may agree with my assessments; some people may not. There have been some claims, and some will say we gave people land, but how secure is the land that people have, even those leases and those offer letters that can be withdrawn if you say the wrong thing and that can be taken from you if you do not follow a certain political party? Are we still not in Rhodesia where land was controlled and managed by a small group of people who used it the way they wanted? If you speak out you get thrown in jail, beaten, tortured, or sometimes killed. What has changed?

I will conclude, in my opinion, and this is probably an unpopular opinion with some of my uncles and fathers who went and fought, that the struggle against the white minority was proper and necessary, but it was hijacked by a small group to perpetuate the very system that initially they were fighting against.