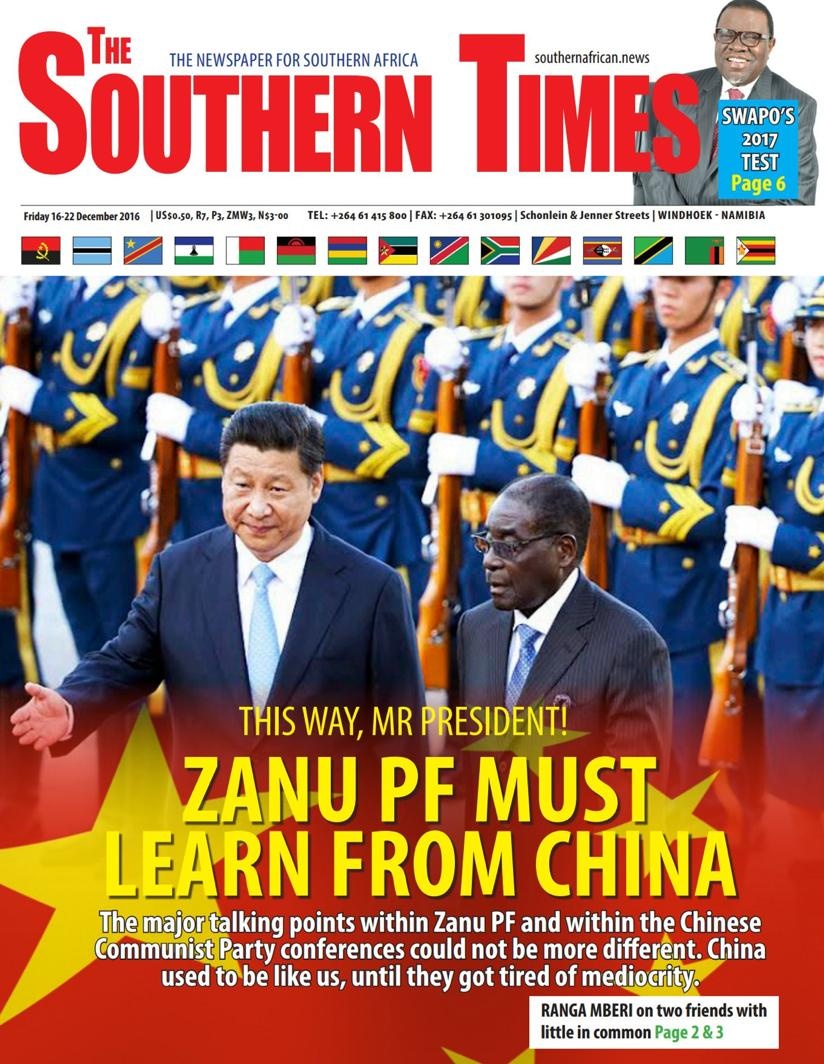

(In December 2016, ZimLive editor Mduduzi Mathuthu, then the editor of The Southern Times newspaper based in Namibia, was dragged over the coals and subsequently fired for publishing this editorial by journalist Ranga Mberi. We republish it following public interest after Zimbabwe’s spokesman for the presidency George Charamba described the publication of the editorial as “a serious diplomatic misstep which infantalised Zimbabwe and national leadership.”

Charamba confirmed it was his call to fire Mathuthu in his “role” as the “shareholder representative” at the publication which was a joint venture between the governments of Zimbabwe and Namibia. Charamba tweeted on October 27, 2020: “Why wield power you don’t deploy against errant employees who go against editorial value?”)

HARARE – In the same week that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) released details on its conference debates, Zimbabwean media were also awash with stories on Zanu PF conference preparations.

Looking at the state of debate in the CCP, and then the level of debate in the Zanu PF provinces, one gets a stark reminder why one of the countries is a world economic power, and the other is struggling.

A bit of background is necessary.

The CCP is the ruling party of China, with a strong hegemony over the country. For decades, it has driven the agenda in China. Through various committees, the CCP directs how China is run, from politics to economic policy.

There are some loose similarities with Zanu PF, a long-time ally of the CCP. Zanu PF too, has a stranglehold on how Zimbabwe is run. The party holds a strong majority in Parliament, which it won back in the 2013 election after having lost it, for the first time ever, in 2008. And, a bit like the CCP, Zanu PF wields the power in Zimbabwe, the result of experienced leadership and also, although Zanu PF opponents will deny it, helped along by a weak and ineffective opposition.

Sadly, that’s where the few similarities between the meetings of these two old friends end.

And nothing best paints the contrasting picture but the difference in the parties’ annual meetings. In October and November, the CCP held its annual conference and a two-day working committee meeting.

This December, the CCP holds its Central Economic Work Conference, where the progress of one of the world’s biggest economies is planned. This conference was preceded by a meeting of the 25-member Politburo last week, where it was announced that the CCP’s economic plan in 2017 would be centred on “seeking progress while maintaining stability”.

A look at what all these meetings have debated is a lesson.

The CCP debated its expectations of economic growth next year, having been content with the 6.7 percent growth expected this year.

While upbeat about its targets, the CCP debated “many outstanding problems”, among them idle capacity and financial risks. They debated how to react to this, with suggestions made on “deepening supply-side structural reforms”.

They debated agricultural reforms, and nurturing new growth drivers. They debated how to unleash consumption, and to attract foreign investment next year. They also debated suggestions on financial support for poverty alleviation, funding for small businesses, and industrial innovation.

China is run on the CCP’s five year plans, the next of which started running in 2016. It is a detailed plan on “the task of stabilising growth, promoting reform, adjusting structure, improving people’s livelihoods and guarding against risks”.

Among the major points of debate within the CCP is what to do with the country’s state owned enterprises.

Three years ago, during the CCP’s 18th Party Central Committee, China introduced a reform plan. It was called the “Guiding Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on Deepening the Reform of State-Owned Enterprises”. It’s a mouthful, but it is a plan that came after much debate, which continues to this day, about how to reform parastatals.

Just like in Zimbabwe, and in many parts of Africa, Chinese parastatals have a big impact on the country’s economy. They employ more than 30 million people. In the first half of 2016, the gross revenue of SOEs reached RMB21.39 trillion (about $3 trillion), more than 60 percent of GDP. So there is massive debate in the Chinese ruling party; do we focus on making them efficient, do we merge them, or do we do away with them entirely?

The debates within the CCP on the economy are endless. My point, however, is not on what the CCP is discussing; it is on the fact that the CCP is actually discussing all this at all.

Now, let’s cross over to Zimbabwe, and weep a little. This week, Zanu PF is holding its own annual conference where, according to the leadership, the party “takes stock” of its progress in meeting the people’s electoral mandate.

However, the major talking points within Zanu PF and within the CCP meetings could not be more different.

The headlines tell the story. One article quoted a senior Zanu PF official “daring malcontents” to try and stir up any debates on power. Another headline celebrated a suggestion that all provinces should have permanent conference venues. And yet another quoted an official boasting that the conference will show that Zanu PF “remains in charge”, as if this was ever in dispute.

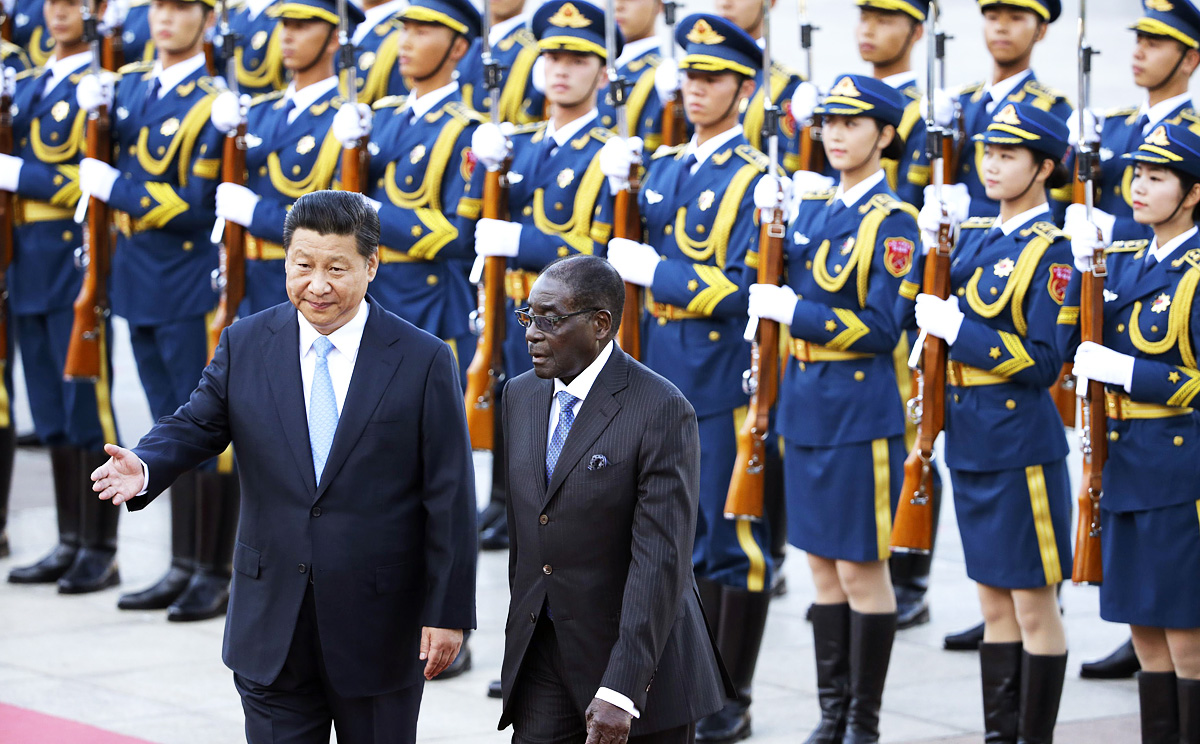

The contrasts with the CCP cannot be any starker. And, no, it is not because the CCP does not have its own contestations for power. In both parties, there is that tussle. While Zanu PF grapples with the “one centre of power” issue, the CCP’s recent meetings also reaffirmed President Xi Jinping as “the core” of the party, a position few in the history of the party have been given.

And yet, what the CCP has done with its strong grip on power is drive China into a global power, despite all the internal power plays that the party has to deal with. Meantime, Zanu PF has so far failed to harness its two-thirds Parliament majority to steer the national agenda, let alone drive the economy out of trouble and meet at least some of its election promises to supporters.

The debate in the CCP’s organs, from its Politburo to the Central Committee, is on issues of substance; how to grow their already powerful economy, how to make the lives of Chinese people better, how to help small businesses, and many such issues of real relevance.

The debate in Zanu PF organs is on issues of individual power and greed; who should have what post, who is the best commissar, who should be suspended, and who doesn’t know how to chant slogans, which slogans are banned, and so forth.

China used to be like us, until they got tired of mediocrity and realised that real global influence comes only with economic clout, and not the slogan-chanting talents, or lack thereof, of the local commissar.

Look; no patient cares about slogans when they are waiting in line for drugs at a rural Masvingo hospital, where the few drugs available are donated by some foreign government. The pupil learning in the mud-and-pole classroom at Bunsiwa in Binga doesn’t really want to know about centres of power, do they? Neither does the unemployed graduate hawking fast-rotting mangoes to travellers out of his tin bucket at Kudzanai Bus Stop in Gweru care too much about which faction is gaining traction.

Maybe one day, Zanu PF conferences will be more like CCP’s. More a platform for relevant debate and agenda setting, and less an annual ritual of deceptive grinning, slogan-chanting and bone-chewing.

Zanu PF has just about as much influence over Zimbabwe as the CCP has over China. However, Zimbabwe’s ruling party has much to learn from CCP; it’s not only about having power, it’s about what you do with it.

This article was originally published by the Southern Times in December 2016