HARARE — Five decades after Zimbabwe ignored the international ban on the pesticide

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, its detrimental effects on the ecological balance of the Zambezi Valley are becoming alarmingly evident.

Perhaps most disturbing has been the discovery of traces of DDT in the breast milk of women living in Nyamhunga, a high density suburb in Kariba, a town on the shores of Lake Kariba.

Despite its well-documented toxicity and the bans in many countries, Zimbabwe continued to rely on DDT for controlling tsetse flies and mosquitoes, citing its cost-effectiveness and efficiency.

However, the long-term consequences of the reliance may have far outweighed the immediate benefits. Zimbabwe only banned the use of DDT in agriculture in 2001.

The pesticide, which works by affecting the nervous system of animals resulting in death, was banned in the West because of its adverse and cumulative effects which can result in a significant decline in biodiversity to complete loss of species.

Despite the warnings, Zimbabwe continued to use the chemical for the control of tsetse fly and mosquitoes, saying it was the cheapest and most effective pesticide.

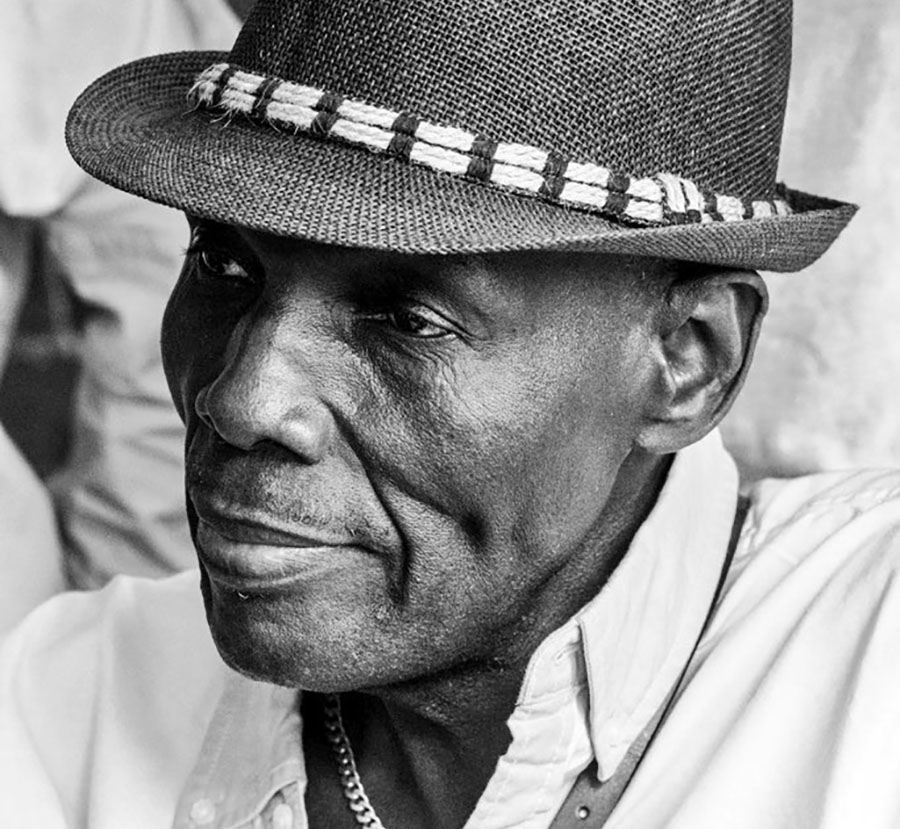

Medical officials at Kariba’s district hospital have initiated studies to assess the impact of DDT on human health. “We analyse pesticide residues in human tissue through autopsies or biopsies, but using breast milk is a convenient alternative. While the results are not conclusive, we are conducting further investigations into DDT levels,” an official said.

Ecological and chemical methods are employed to control fly populations in the Zambezi Valley. Ecological strategies involve destroying habitats by clearing riverine vegetation and eliminating wild animals that serve as food sources for tsetse flies.

On the chemical front, chlorinated hydrocarbons like DDT had been used since 1967 by the Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Control Branch in the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development and by the Ministry of Health and Child Care for malaria control since 1972.

Between 1978 and 1989, DDT applications for tsetse control averaged 200 tons annually, peaking at 442 tons in 1986. From 1968 to 1979, more than 36 000 square kilometres were treated with DDT, followed by an additional 32 550 square kilometres from 1979 to 1990. These statistics highlight the extensive use of DDT, particularly in the Zambezi Valley, where some areas have been treated up to 13 times.

The Blair Research Laboratory in the Ministry of Health and Child Care confirms that there are alternatives to DDT. “While alternative chemicals exist, it’s premature to determine their long-term effectiveness due to developing pest resistance,” an official noted.

The impact of DDT extends beyond human health. Dr Lightone Marufu, an Aquatic Ecologist in the Biological Sciences Department at the University Of Zimbabwe and also the departmental representative at the University of Zimbabwe’s Lake Kariba Research Station, emphasises the pesticide’s harmful effects on local wildlife. “DDT can cause thinning of eggshells in birds of prey and crocodiles possibly leading to reproductive failures and consequently biodiversity losses’’

Moreover, studies on the African Goshawk indicate a significant population decline likely to be linked to DDT spraying for tsetse fly control. Fish populations in Lake Kariba have also suffered, with elevated DDT residues found in fish from treated areas. “DDT affects sex hormones, leading to imbalances in wildlife,” Dr Marufu adds.

A study by two ecologists from the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority revealed that out of 22 woodland bird species, eight were significantly less abundant in areas treated with DDT. This decline underscores the broader ecological consequences of persistent pesticide use.

Although DDT use has been banned in the country since 2001 for agricultural purposes, it is still allowed for certain public health purposes, particularly for vector control in malaria prevention. The country’s regulations reflect a commitment to managing health risks while addressing environmental concerns.

\

In Zimbabwe, the legacy of DDT highlights a complex struggle between public health and environmental sustainability. The Zambezi Valley, a vital ecosystem supporting diverse wildlife and local communities, faces an uncertain future as the balance tips further towards ecological degradation.

Dr Marufu however, said: ‘’It will also be important to explore the possibility of bioremediation to remove or reduce DDT from the environment (soil and water),’’ adding that there is a great need to use environmentally friendly control methods against pests. ‘’But this will need partnership and cooperation among relevant stakeholders. Policy makers should be encouraged to consider human and ecosystem health on the short to long- term basis.’’

As the nation grapples with these challenges, the question remains: was the continued use of DDT worth the cost to health and biodiversity? Without urgent action to reevaluate pest control strategies, Zimbabwe risks not only the health of its people but also the integrity of its natural environment. – New Ziana