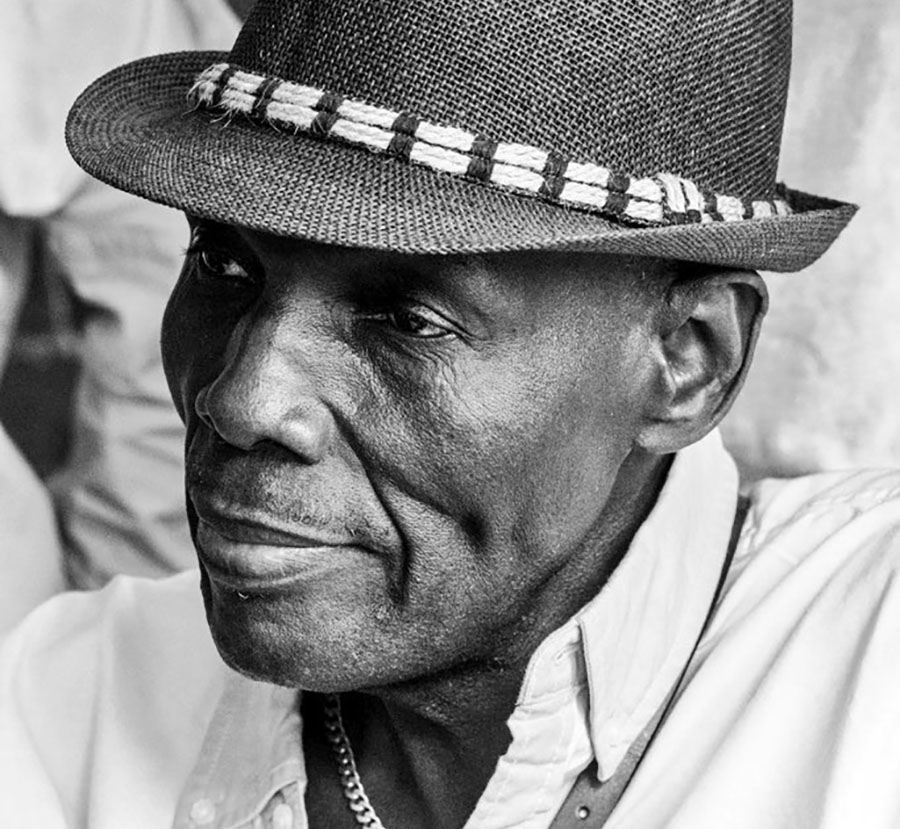

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa – On Friday, July 24, I lost a little brother, Sibangilizwe Ndlovu to Covid-19. In the past few weeks, I have been chiding him especially and many others for many Covid-19 indiscretions when he posted pictures of himself on social media. It is painfully ironic that Covid-19 took him.

I called his wife, Getrude, and cried with her, I cried with his brother Elton Ndlovu and every friend I spoke with. I can’t be there. I can’t and won’t be at the funeral. I can’t and won’t say a proper goodbye. How does one find closure? Such a brilliant life cut short.

This is how our story ends. But where did it all start?

One day in 1997 or so when I was a young lawyer at Coghlan, Welsh and Guest in Harare, I attended the inaugural Walter Kamba Memorial Lecture at the University of Zimbabwe. I think Edison Zvobgo was the Speaker. I would later be speaker in the same prestigious lecture in 2018. As I waited outside to enter the lecture theatre, a scrawny young man approached me and said, ‘Bhudi, awusangazi, nginguSibangilizwe. Ngikwazela eTredgold, ecourt. I’m studying law.” I strained my memory and said, ‘woright… unjani mnawami? Uku what year?’ He told me. Gave me his room number at Complex 3 residence which I promptly forgot.

A couple of months later, I was at the Law Faculty for something I can’t remember now and again met Sibangilizwe. This time we talked some more and tennis came up. We agreed to play. Until then, I occasionally played at the Old Mutual Club in Emerald Hill where my brother Busi Mafuthengwe Malunga was an HR Executive. After several failed appointments, we played once.

Then one day out of the blue he called me at the office. He apologised for doing so out of the blue and for the onerous request he was about to make. The university authorities had just ordered the university closed due to student unrest and asked everyone to leave within an hour. He had nowhere to go. No relative in Harare. He only knew me. “Would I be able to come and pick him up? And could he please leave his bags at my flat as he intended to catch mbombela (economy class) train to Bulawayo that evening?” He would spend the day in town waiting for 9PM when the train leaves. I asked him to hold on and checked whether I had any appointments and then told him I was on the way.

After picking him up we drove to my flat where I told him I had to rush back to work and told him to find something in the fridge to eat and I would see him after work. He protested and said he wanted a lift into town instead to wait for the train there. I insisted that we would talk about this later when I got back from work and left him at the flat.

The university remained closed for almost eight months during which me and Sibangilizwe lived together. It was a wonderful time. I learned he was the brightest student in his class, secured an internship place for him at Coghlan only to discover Wintertons had scooped him up already. Later, when I was searching for a job in South Africa, he called me out of the blue.

He had just joined the UN Mission in Kosovo and was distraught to hear I was unemployed after an unfortunate experience in Botswana. He insisted I join the UN and connected me to Luke Mhlaba, who had briefly been my constitutional law lecturer in the first year. Luke was now a veteran UN lawyer having served with Professor Reg Austin in the UN mission in Cambodia. Luke walked me through the application process and the range of available UN missions. I applied to all of them and got a job in East Timor, where I had the fortune of finding Andrew Ladley, who was Luke’s fellow classmate and professional colleague. Andrew helped me learn the UN ropes.

Within months of joining the UN, Sibangilizwe would buy a house in Ilanda and bug me daily to buy the house next door. He would even negotiate the price.

He was like a young brother. There is no moment, high and low that we have passed and not shared in the past 23 years. I spoke of our life together and how we met at his 40th birthday party a few years ago and he kept saying “sokukwanile, thula phela bro, sukhuluma kakhulu!” All this while tears streamed down his cheeks. It’s me who’s crying now. How does one explain to Onika and Dabiswa that their father is gone, and never coming back?

He was posted to Sudan so the last real opportunity we had was when we partied together on Long Street, Cape Town, last year. He refused to let me buy any drink, insisting: “Bro, kuthenga mina lamuhla please.”

I am especially outraged to hear that the ambulance that was ordered for him at 12 midday only arrived at 4AM the following morning. It is safe to say that Zimbabwe and not Covid-19 caused his death, because he may have made it had our health system not been completely destroyed by Zanu PF. Yes… it is political!

Hamba kahle Boyz, Jimmy, Jimango.

See you on the other side!

(Sibangilizwe Ndlovu: April 26, 1976 – July 24, 2020)

Sipho Malunga is the executive director of the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA)