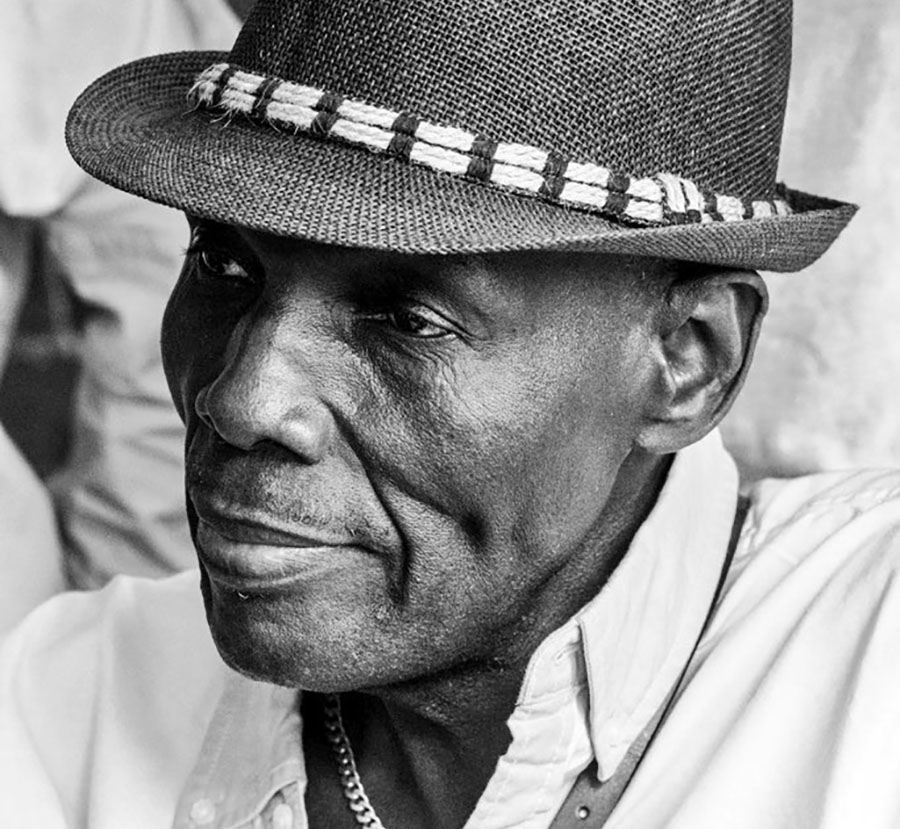

BELVEDERE TEACHERS’ COLLEGE, Harare – My alarm rings at exactly 8.50AM. I quickly remember that I have to collect my packed breakfast at 9AM. I jump out of three small mattresses feeling some back pains. It could just be jetlag; I console myself though deep-down I know my body pains are as a result of the springless bed which could not carry my average body.

As I leave my room, I remember that have to wipe my face. No water. And then there is a mask which I have to put on. I can feel the stench of my old breath on the mask which I only removed before I slept the day before, having worn it for more than eight hours.

Abandoning the idea of wiping my face, I quickly rush down to collect my breakfast. I meet other “inmates” on my way out. We are rushing for the same thing. I try to maintain a six-feet distance from the person in front. I get worried when I realise there are three more people behind me. They shuffle closer to me with complete disregard of social distancing guidelines. I wonder why people from the United Kingdom, one of the world’s coronavirus-hit countries, are so reckless about something they should otherwise know better. I quickly remember that some of these people from cruise ships. They have been staying together for several months. They are family. They don’t see the need for social distancing when they have been staying together all along. In fact, they don’t accept that they are from United Kingdom, as they have been branded by government spokesman Nick Mangwana. They have been in the sea, they say, and not the United Kingdom.

As I collect my breakfast, wrapped in a black, transparent plastic bag from a round wooden table placed strategically in between hostels, I notice caterers standing at a distance. The distance is not six feet. No. It’s about 50 meters. They want to be safe. They have been told people from overseas are as dangerous as they come, as they are the common carriers of the corovirus. I quickly dash back to my room, trying by all means to avoid mingling with other residents. After all, before I travelled back to Zimbabwe, I had been in quarantine for over a month, so this is nothing new for me.

It’s now midday and lunch will be served at 1PM using the same modus operandi: drop and watch from a distance as Covid-19 suspects collect their food packs and leave. I get worried. My worry has nothing to do with the menu. No. This is my least of worries. I’m worried because I last saw medical personnel a day before, when they collected our samples for testing. To make matters worse, I don’t even know who to call should I need emergency medical services. The crew that attended to us at the airport, “thoroughly” screening us has disappeared. No word. And now it’s another day; no one has come even just to check our temperatures. After all. this the reason we are here: to be monitored for the coronavirus, at least according to what government authorities have been repeatedly saying.

Well, I forget about this thought and move to the next. Results. We were told, or at least this is what I read in the news before I travelled, that all returning residents are rapidly tested upon arrival. No, it’s not true. In fact, if you’re a returning resident from overseas you’re not rapidly tested. Instead, you get a nasopharyngeal test whose results can come between 24 and 48 hours. If you’re lucky, you might learn about the results on Twitter, before you’re told about your Covid-19 status.

It’s exactly 3PM. A senior government official who had addressed us the previous day comes. He greets everyone, his tone calm, a sharp contrast with the previous encounter. Charm offensive. He gives feedback about his earlier promise to relocate us to a better facility. The feedback is negative. The University of Zimbabwe cannot house us, he says.

“We’re now considering other options. If you can’t stay here, we will have to move you to a remote facility, perhaps in Chimanimani,” he says. Everyone quickly responds: “No! If it means taking us to a remote facility we better stay here. Just improve the conditions,” inmates say.

The official, visibly happy with his small victory, retorts: “We’ll take care of all your needs. We will address the water issue.”

Everyone, the inmates are assuaged. Deep down, I heave a sigh of relief. I know my expose in response to lies by government spin doctor Nick Mangwana has played the trick: authorities are now more willing to listen and deliver on their basic obligation: ensuring that all returning citizens under the custody of the government are treated humanely.

It’s exactly 7PM in the evening and it’s about 45 minutes after we had our super — a decent meal by Zimbabwean standards. An inmate knocks at my door and tells me that I have to go and collect my parcel downstairs. I don my mask and dash downstairs. The formula has not changed. The parcel has been placed in a round table and the givers are standing at a distance ensuring everyone has collected their pack. I tiptoe to the table, carefully looking in all directions to ensure that long lenses of spying camera don’t catch me. I pick the parcel — a green soap, toothpaste, bath soap and a 2-litre juice. I force a smile. So the regime can deliver when pushed into a corner.

I retire to bed. The next day awaits me: my Covid-19 status, an impending visit by the minister of health, the possibility of relocation. All these thoughts melt away as I take a deep slumber.